I hear you.

The last couple of entries have met with Noo! I'm feeling so seen right now!! and Yeesh, this hit me right in the first draft! and Now I’m worried. (See yesterday’s comments.)

Quite a few people have come back to me, saying that this is how they write. They work on separate sections, perhaps over a long period of time, and then they begin to assemble them. To try to assemble them.

(I’ve often worked in this way, too.)

As an approach to a zero or first draft, and to finding out what a book is, or might be, it’s got many pluses.

You give yourself the chance to surprise and maybe even delight yourself.

You’re able to follow odd voices and their odd hints.

You avoid pressuring your first thoughts to be anything like what you’re going to end up with.

But the likelihood is that the real first draft is going to involve a picking out of a few choice threads from the big lovely mess you’ve made.

The problems can start when you think, I’ve written 60,000 words — I’m 60,000 words into a novel.

You’re not, however much you might hope you are.

With this approach, the likelihood is that only 3 or 4,000 of those words will end up in the finished book, and in altered form.

The biggest danger writers who work in this way face is ending up with a patchwork manuscript by trying to keep 40,000 of those words.

The rest of their writing process, after the initial draft, can become a kind of desperate self-justification. This has to be in here because, well, it just has to be in here.

(Again, I’m looking at myself.)

Good days — days on which no-one bothered you and you wrote 3,000 words — can be the worst days of all. These create flowing, silky prose that slides easily past events that probably needed a lot more tug.

How are these smooth sections — bank holiday sections, writing retreat sections — ever going to fit with exhausted Saturday-after-a-family-lunch sections, or itchy up-at-5.30-am-to-get-something-down sentences?

Well, they’re not. Not unless you’re an experienced novelist holding on steadily to darning a texture of prose that you know you can achieve in almost any writing situation.

Let’s not forget, you’re telling a story. You’re bring the reader into that time and rhythm.

Story-time is something you as a writer re-enter, when you re-enter the story you are telling.

What good writers learn is a way of re-entering the same story-time they left, perhaps six days ago.

They sit down and they’re back.

What most writers need to learn is a way of not creating a patchwork, where each panel is a different shape to all the others, and cut from an entirely different cloth.

This isn’t to say, stretching the metaphor a bit more, that all stories or novels should be blankets of a single colour knitted from a single wool. But one of the skills a writer needs to learn is consistency — consistency of POV, consistency of tone. It is far easier to make a novel that has a satisfying structure from sections of writing that are from roughly the same material.

That’s why, yesterday, I advised against learning to write a novel by writing a multiple viewpoint novel set in multiple places and times.

A regular writing discipline will certainly help you to achieve consistency in what you are writing — especially if what you’re writing is a novel. Same place. Same hours. But such regularity may not be available to you, life-wise, and so you’ll need to find ways of conjuring it.

That may mean keeping your circumstances as identical as possible. Using the same pen or pencil. Putting on the same playlist. Dabbing the same scent on your neck. Wearing the same soft clothes.

Or it may mean sticking close to the grain of a voice that you either know already (because it’s based on a real person) or you come to know (because you’ve written it for a while).

Danger comes if, alongside your writing, you are reading widely and wildly.

One day, you’ve just been enjoying and being influenced by Raymond Carver, and what you produce is rough canvas. Cut those adjectives. Three days later, you’ve been at the Oscar Wilde and a little velvet has slipped out. Just a couple of aphorisms. Next follows Toni Morrison, who tips you towards an intricate dark weave if she doesn’t overawe you completely. On holiday, you switch to a diet of thrillers, and afterwards produce a sheet of marvellously waterproof kevlar. Then you return to work and things get busy, a couple of Facebook links is all you see, and papery notes come out of you — for later working up into silk.

Familiar? It is for me.

Something very similar can happen if you are reading different writing manuals or following different blogs. One writer (not me) advises splurging a really fast first draft, another (not me) suggests doing lots of research first, and a third (perhaps me) tempts you into writing a short story to explore a particular character.

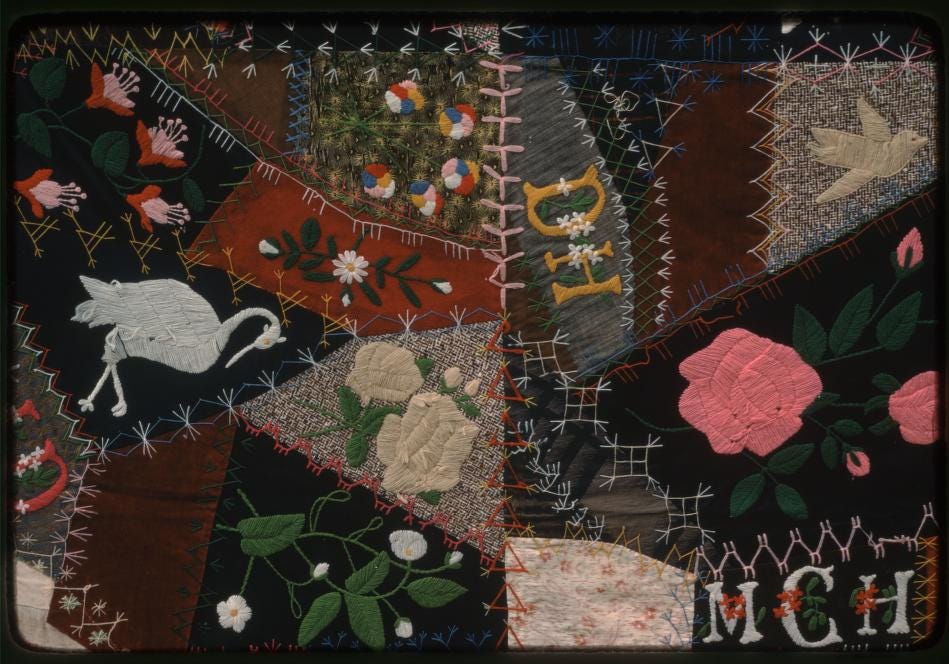

If your patchwork develops into a novel-length thing, it will have have become a quilt.

Quilts are wonderful. As an artform, they work by resolving and unifying when you’re a certain distance away from them. Quilts look best from a few paces back, when you’re able to take in the patterning that this piece over here comes from the same fabric as that over there. It doesn’t matter that this hexagon shows flowers and that one birds, and it doesn’t matter this one’s pink and another’s bright green. What a quilt is allows them all to come equally in. (And the viewer can also delight in looking closely at details.)

But for a quilt to be well made and long lasting, there needs to be more than a little bit of judgement in the materials. The stitching needs to bring consistency. It is very challenging to make a quilt of cotton, cornflakes, rubber sheeting and the wings of a fifty bluebottles. They will fall apart from one another too easily, although creating them at those different times was immensely free and enjoyable.

Within a first or third person omniscient narration, there is likely to be a basic consistency of materials. A first or third person voice may fit itself to its subject, may alter sympathetically when writing about a baby or about arthritis, or when covering about an incident of two seconds’ length and a marriage of fifty years, but it is not likely to change substance entirely.

Multiple narrator novels are more likely to end up as quilts of rubber sheet and cotton (let’s forget the cornflakes and who mentioned flies?).

But even this can work when these few steps back are taken by the viewer. The transition from one material to another, from one voice and tone and density to another, may be extremely jarring the first time it happens. And some viewers may turn away. The second time, though, it will be familiar and by the third time it will have become part of a rhythm. By the end of the novel, the presence in the same work of such different speakers and writers will most likely seem to be entirely harmonious. Even cotton and rubber.

But that reader has been extremely indulgent, and it’s almost certain they’re a big fan of very oddly constituted quilts.

Has this become too much? Is the quilt thing overstretched?

What I’m trying to get across is, yes, that this way of writing is often about doing too much and then, later, trying to bring it all together.

Which is really really really really difficult. And painful. And time-consuming.

That’s why I don’t advise it as a way to begin writing novels. That’s why, however dismayingly, I advise against it.