For the next seven days, young-Toby writes nothing in his big blue 1990 diary. And so now seems like a good time for us to see what he has really been up to.

Fictionally.

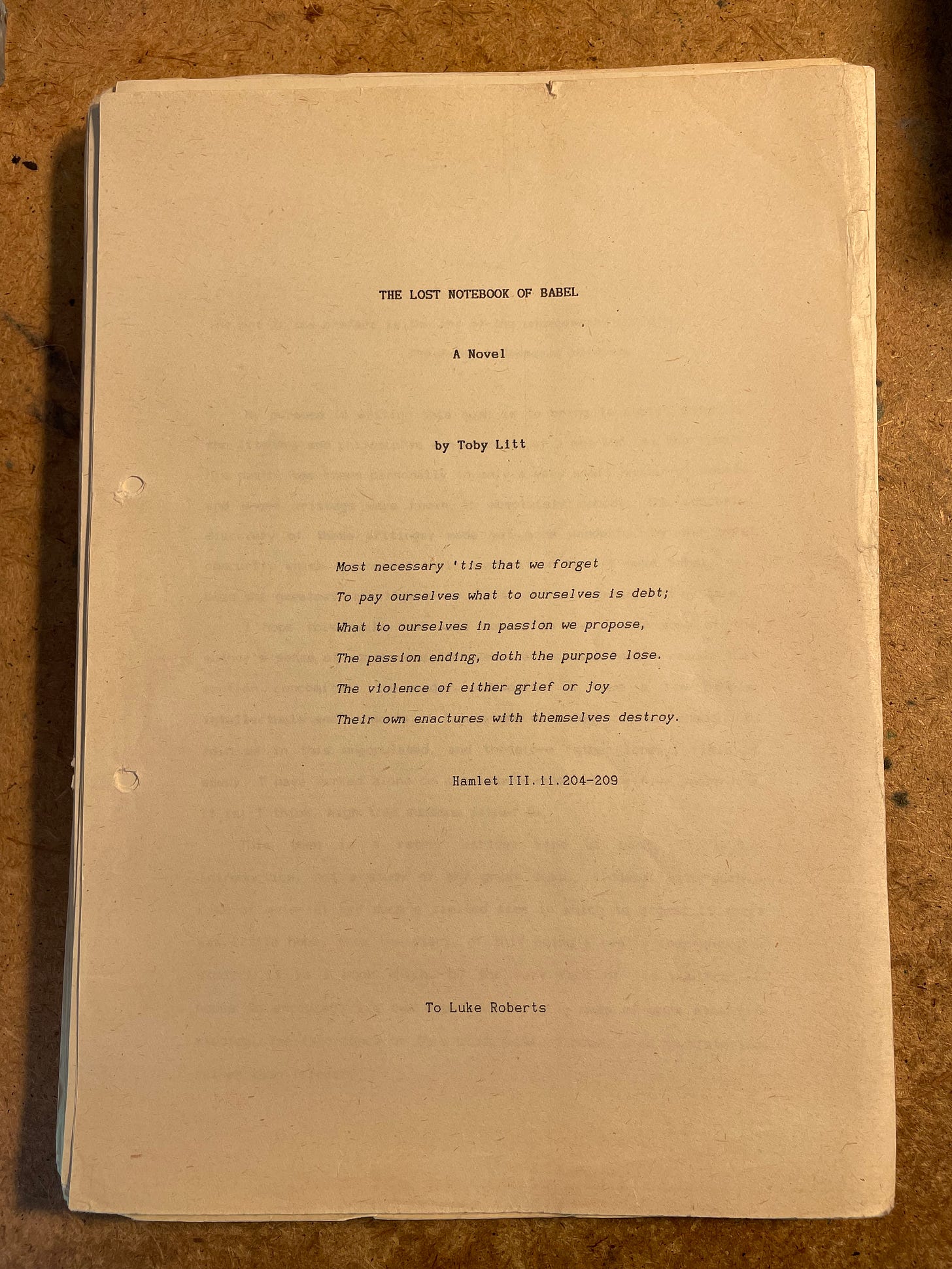

I thought that the typescript of his first, unpublished novel was in a plastic storage box in a pile of plastic storage boxes in the cellar. And I thought I would leave it there. Then I remembered it was in a buff cardboard folder in a steel filing cabinet four steps behind me.

Since I stopped sending the novel out to publishers, in perhaps 1993, I haven’t looked at it.

I’m not going to share the whole thing here. But if you’ve been following young-Toby up until now, you’re probably a little curious about what he’s been working on, and about whether it’s any good.

For the next week, I’ll be sharing some short extracts from the beginning of the book which never became a book.

But it did, thanks to Sally Abbey, a junior editor at Penguin, escape the slush pile. It even, after a complete rewrite, made it as far as an acquisition meeting — at which it was considered for publication, then rejected. Sally phoned to tell me the disappointing news. A year or so of hope, ended.

If my first attempt at a novel hadn’t received this encouragement, this glimpse of possible success, I might have concentrated wholly on poetry.

I used to get asked, Did anybody discover you?

There were various candidates for an answer: my favourite English teacher; Terence Blacker; Malcolm Bradbury; my first agent, Mic Cheetham.

But Sally Abbey is the first person who read my fiction cold, and saw something in it, and gave me a reason to keep going.

Years later, I did meet her at a launch party. (She had become, among other things, Sarah Water’s editor at Virago.) I was, I hope, gracious and polite — but I was a bit grumpy; I still wished Penguin had said yes.

Today, I am very very very glad Penguin said no.

My first book, Adventures in Capitalism, came out six years after I first submitted a novel to a publisher. Six years during which I wrote three and a half more novels.

Adventures was a much better book than Babel. It made more of a splash. It set me going. But most importantly, it was a very diverse collection of short stories. This meant I wasn’t pigeonholed as a certain kind of writer. I could follow Adventures with whatever I wanted, and didn’t have to consider keeping the same readers generically happy.

If I’d published Babel first, I’d have been considered straight literary fiction.

That’s what, retyping these opening pages, I am most aware of.

Young-Toby is writing — or trying to write — something like Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire or (although he hasn’t read it) Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus.

Doctor Faustus begins —

I wish to state quite definitely that it is by no means out of any wish to bring my own personality into the foreground that I preface with a few words about myself and my affairs this report on the life of the departed Adrian Leverkühn. What I here set down is the first and assuredly very premature biography of that beloved fellow-creature and musician of genius, so afflicted by fate, lifted up so high, only to be so frightfully cast down.

The Lost Notebook of Babel makes the same gambit.

Don’t look at me (look at me).

Pale Fire, a direct influence, has this near the start —

I must now explain how Pale Fire came to be edited by me.

Immediately after my dear friend’s death I prevailed on his distraught widow to forelay and defeat the commercial passions and academic intrigues that were bound to come swirling around her husband’s manuscript (transferred by me to a safe spot even before his body had reached the grave) by signing an agreement to the effect that he had turned over the manuscript to me; that I would have it published without delay, with my commentary, by a firm of my choice; that all profits, except the publisher’s percentage, would accrue to her; and that on publication day the manuscript would be handed over to the Library of Congress for permanent preservation. I defy any serious critic to find this contract unfair. Nevertheless, it has been called (by Shade’s former lawyer) ‘a fantastic farrago of evil,’…

That gambit here is more convoluted.

Don’t look at me (look at me); I’m not shifty (I’m completely untrustworthy).

You’ll see tomorrow how the editor-within-the-text of The Lost Notebook of Babel makes his start.

And you’ll see if young-Toby is anything of a writer.