This is fun.

In Restaurant at the End of the Universe, Douglas Adams invents a new POV — a tense for future events that have already happened, repeatedly, and are also happening at this precise moment, too.

That’s because this tense is referring to a place — a dining establishment — that, because of time travel, visitors can eat at, or have already eaten at, or are currently eating at, which exists perpetually in the lead up to the very last moment of all, which has already occurred multiple times.

Something like that.

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe is one of the most extraordinary ventures in the entire history of catering. It is built on the fragmented remains of an eventually ruined planet which is (wioll haven be) enclosed in a vast time bubble and projected forward in time to the precise moment of the End of the Universe. This is, many would say, impossible. In it, guests take (willan on-take) their places at table and eat (willan on-eat) sumptuous meals whilst watching (willing watchen) the whole of creation explode around them. This is, many would say, equally impossible. You can arrive (mayan arivan on-when) for any sitting you like without prior (late fore-when) reservation because you can book retrospectively, as it were when you return to your own time. (you can have on-book haventa forewhen presooning returningwenta retrohome.) This is, many would now insist, absolutely impossible. At the Restaurant you can meet and dine with (mayan meetan con with dinan on when) a fascinating cross-section of the entire population of space and time. This, it can be explained patiently, is also impossible.

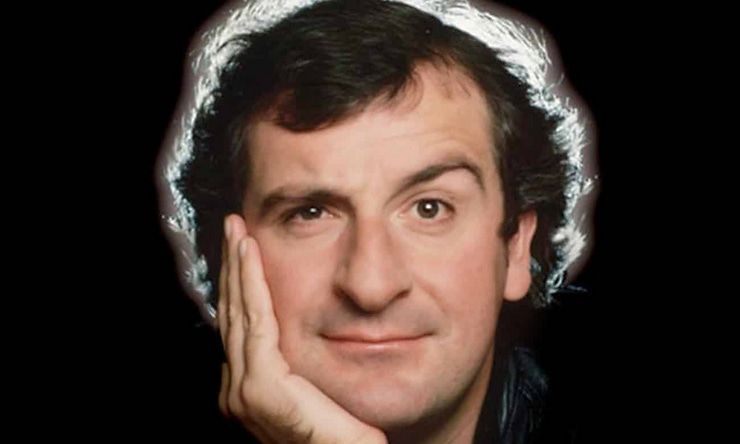

The young Adams studied English at St John’s College, Cambridge in the early 1970s. And here he is clearly remembering his Anglo-Saxon, or Old English.

And making a joke of it.

For example, ‘willan on-take’.

‘Willan’ is the Anglo-Saxon word for ‘to wish’. But is warned against as a false friend, because students are likely to remember and translate it as ‘to will’.

Adams might also have been thinking of ‘whilom’ — (which in Old English was ‘hwílum’) meaning ‘while’ but also ‘once upon a time’, ‘at some past time’ and yet also perhaps later on in its development, ‘at a future time’.

Perfect.

From my research, it seems Anglo-Saxon doesn’t have a future tense, and so the idea of wishing something was a good way of alluding to events that hadn’t happened yet. (Also, present day English doesn’t have a separate future tense — as I have been told several times when putting together the Complete Guide.)

In Old English, ‘-an’ is the usual ending of a verb’s infinitive verb (‘[to] blah’ would be ‘[to] blahan’).

‘On’ has a similar meaning in Anglo-Saxon as in modern English. It means ‘within, during’. I think Adams was thinking of ‘on-going’. The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, in his depiction, is ongoing.

‘Take’ is ‘take’.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘forewhen’ doesn’t exist, but it should have done for some time — especially if time travel is possible.

And what a lovely word is ‘presooning’.

All of which suggests Douglas Adams (bless him) was amusing himself with the sound of making sense whilst not constructing anything as exhausting or time-consuming as a verb table.

English can become very complicated in referring to the future engaging with its own past which hasn’t yet taken place. For example, ‘I will have for some time been regretfully anticipating X’. Conceivably, this could be mashed up into ‘I wilhofbinsadforelooking X’ — which could, with use, become ‘I wilfsad X’.

Possibly.

The fact that a word doesn’t exist isn’t proof that we don’t need it.

English lacks a word for ‘youngest of two younger brothers’, for example. And has to make do with ‘big sister’ for ‘older sister’, even if there are three other siblings in between. I suppose there is ‘oldest sister’.

If you’ve come across any other attempts to create a proper future tense for English, or would like to share your own, there’s no time like the present.

My hero, Douglas Adams!