This was a question that came up when I was taking the Creative Writing MA at the University of East Anglia.

One of my fellow students wanted one of their characters to be a genius, and they were wondering if this could be done — and, assuming it was, how this could be done.

It’s a very good point.

But I’m not sure I’ve ever discussed it again.

The challenge most obviously arises when you’re attempting to write in the voice of a writer who is a themselves genius. (Leaving aside whether there are such beings.)

I sort of did this with a character in my first, unpublished novel.

Their writings, though, as I included them, were only their notebook scribblings, not finished poems.

If you are conveying to your readers that your main character is a great poet, and you’re quoting their poems, then they better be great poems.

AS Byatt tries something like this with the verses in Possession. But her way round it is to set the novel historically, and to write what is obvious pastiche.

The problem here is that poets of the past occupy a particular cultural space. There’s a Elizabeth Barrett Browning space, a Tennyson, a Matthew Arnold. Together, they make up the whole literary scene of that time.

If you’re saying your Victorian poet was a genius, sadly undiscovered, then they don’t need to exist believably within the culture of that time. But if you’re showing them as famous, beloved, and therefore influential, imitated, you will have a much harder job making them credible.

There’s a similar problem with fictional pop and rock stars. The main character in Don Delillo’s Great Jones Street is a bit Jagger, a bit Bowie, a bit Dylan, but never convincingly exists alongside them in the 1970s — an alternative reality is created, in which he (Bucky Wunderlick) exists and in which we believe slightly less.

The composer Adrian Leverkühn in Thomas Mann’s Dr Faustus is a more solidly depicted genius, but even so they are seen in a kind of double vision, overlapping with the reality of Arnold Schoenberg.

It is easier to depict, say, a maths genius — and easier still if the novel is set in the past. All you have to do is attribute a later mathematical breakthrough to them, several decades before it was actually made. The equations are there, pre-existing, for you to not quote but to summarize, and call beautiful, elegant and godlike.

This anachronism is unlikely to convince a readership of mathematicians, who are aware of all the other research that preceded and supported the singular eureka moment you’ve stolen for your character, but they are not going to cause you as much of a problem as a gang of angry Victorianists — or, more likely, a lot of good readers who know absolutely not-great poetry when they see it.

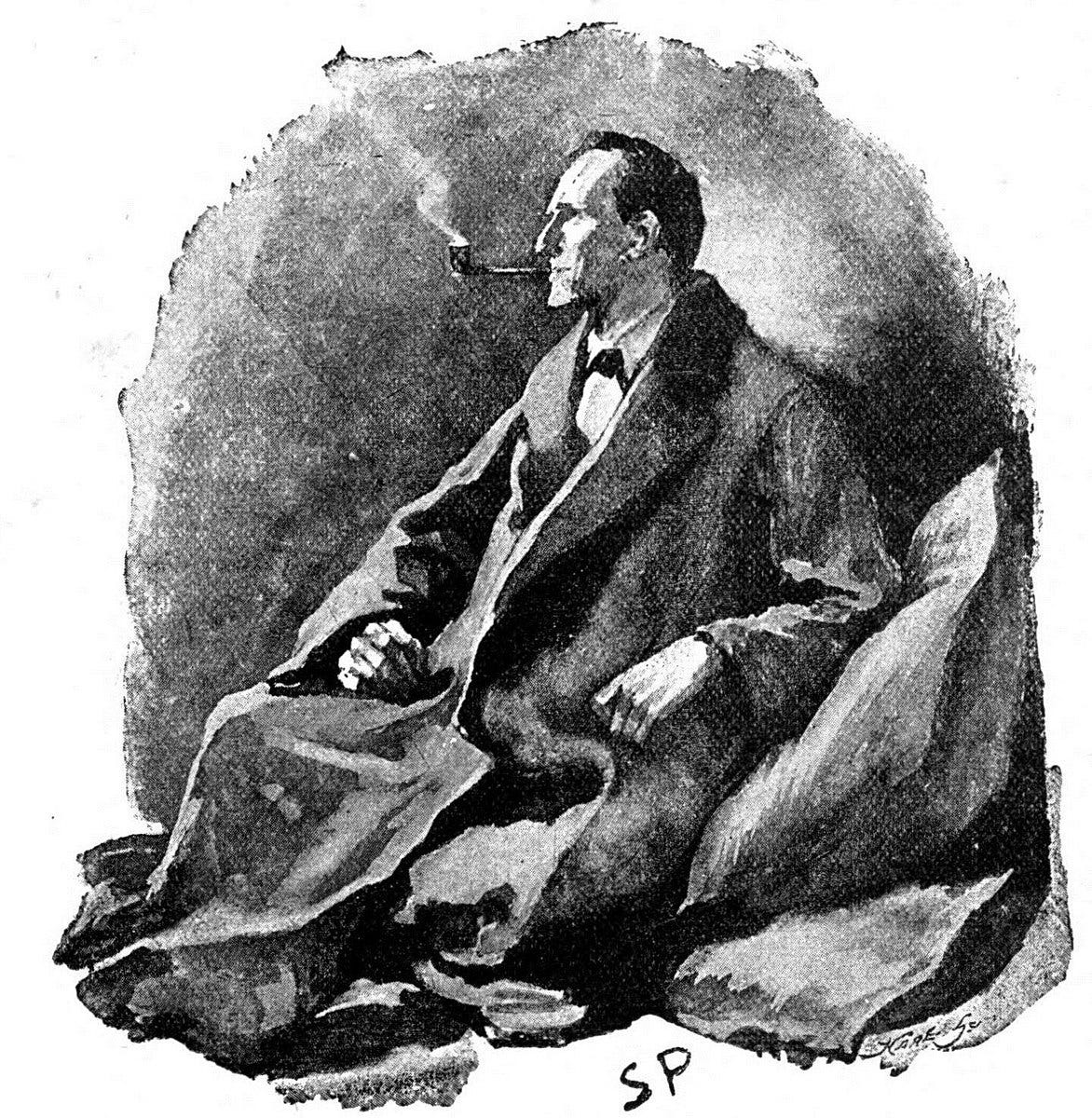

The most obvious example of a writer creating a character more intelligent than them is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes.

Yes, Conan Doyle has to invent many of the details of the forensic science and deductive reasoning that Holmes employs. In that sense, he has to be clever enough to have those insights and follow those chains of logic. However, Conan Doyle is able to game the temporality of his stories. Not only can he start with an outrageous crime and then work out a brilliant way of solving it, he can also make sure — however ropey Holmes’ claims sometimes are— that the great detective is almost invariably correct. The alternate explanations as to why a character might be dressed as they are, with that kind of dirt on their hands, simply aren’t given the chance to exist in 22b Baker Street.

(Moriarty is another case. All Conan Doyle needs to do, once he’s written Holmes, is say that there exists an even more brilliant man.)

A similar gaming of temporality is available to any writer who wants to depict a genius, more sensitive to their surroundings than normal folk.

Equally, you can have a character be psychic, and predict the future, and that future manifest exactly as they predicted. (Though that’ll probably kill your story — so have them be a bit wrong, or not have seen something.)

The simplest answer to my fellow student’s question is that novelists are generalists. They tend to know a bit about a lot of diverse and most of the time useless things. For example, they know something about contemporary fashions — enough to be able to do a first draft describing a Tiktok influencer getting out of a limo. After this, the novelist will do their online research, but their first guess might be good enough.

Same goes for whatever they are likely to want to put in a novel. Writers are not always writing what they know, but they are writing what they have some vague sense exists in that direction over there.

That’s enough.

Novelists already have some idea how very intelligent people talk — their quickness, their speech patterns, the ways they try to make themselves comprehensible or approachable, their lapses into the completely opaque.

Unlike the geniuses, novelists can come at the same piece of dialogue six or seven times, trying to be more intelligent with each pass.

And if all this doesn’t work, writers can always get the brightest person they know to read those parts of the draft where the genius is seen in action.

So, yes — it can be done.

Can you think of who has done it best?

The Sherlock Holmes structure, where an everyman POV narrator watches the genius, must be easier to write than a genius POV. Carol O'Connell's Mallory crime books do the same - the possibly genius, possibly sociopathic hacker-skilled cop Kathy is always seen through the eyes of others. So we don't know HOW she hacks into things (nor what her real emotions are).

On this I only need study my daughters. I actually said to one of them last week (when she was assisting me at work) how impressive, she'd solved something cleverly and I said Do you think you're more intelligent than me? Without looking up from her laptop she nodded in the 'yes, that's universally understood' - ha. X