Before I visited China in 2003, I sat down and wrote a list of sentences all beginning with the words ‘I expect’.

In doing this (as detailed yesterday) I was varying a form invented by the American artist Joe Brainard. In 1970, he published a short book called I remember in which each paragraph began with those two simple words.

For example: ‘I remember the only time I ever saw my mother cry. I was eating apricot pie.’

I remember was a success, and Joe Brainard followed it with More I remember, More I remember more and I remember Christmas.

However, I first came across the form in a book about the French literary group known as OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, or Workshop for Potential Literature).

One of the central OuLiPo writers was Georges Perec, author of Life: A User’s Manual. He heard about Brainard’s new literary form from Harry Mathews, the only American member of the group.

In 1978, Perec published a book about his childhood using the I remember form called. He called it, as you would expect, Je me souviens.

As far as I know, I am the first writer to combine the I remember with a preceding I expect. (I’m not a member of OuLiPo.)

A brief explanation of why I tried this experiment will be posted tomorrow, as a post-script.

Firstly, though, I should set out the self-imposed conditions and limitations.

1. All of I expect was written several months before I went to China.

2. Some of I remember was written in China but most in the weeks after I returned to England.

3. I didn’t take I expect with me to China, nor did I look at it again before writing I remember.

4. None of either I expect or I remember was rewritten to make me look better, or worse.

5. A few entries were cut entirely.

6. The bulk of the entries do not appear in the order in which they were written.

I expect

I expect inoculations, malaria tablets.

I expect, as I usually do when I set off to travel, that I will anticipate dying at least fifteen times; on take-off, over the ocean, on landing, in a bomb at the airport, etc.

I expect to worry about what to pack, and to forget to pack something very obvious and necessary. Nail-clippers.

I expect speeches of humorous welcome.

I expect to spend much of my time absurdly worrying about whether I have committed some gross social faux-pas which those around me are too polite even to acknowledge among themselves in private afterwards.

I expect not to go anywhere that Westerners are particularly much of a novelty.

I expect expectoration – sniffling, sniffing, hawking, spitting, gobbing.

I expect very few NO SMOKING environments.

I expect to remember Kafka’s parables.

I expect to have difficulties with dragons, their aesthetics.

I expect to feel reasonably tall.

I expect ‘no okay only great and awful’.

I expect culture-shock, and will be disappointed if I don’t fall victim to it.

I expect, as was described to me by Yang Lian, an ‘ocean of food’, which will include roast dog, the brains of a live monkey, freshly killed (i.e., in front of my eyes) chicken, dangerous chilli-type-things.

I expect to feel hopelessly caught up in my own Orientalisms.

I expect to feel like a prig at least once an evening, and a prick at least once a day.

I expect my beard to be unwelcome, and I will probably shave it off.

I expect to develop the usual culturally inculcated (Nationalistic) food-cravings, through which I will develop my solidarity with the other writers: toast, marmalade, Marmite, English mustard, HP Sauce, baked beans, chips, chips, fish and chips.

I expect the trains to be very large and our compartments (I expect compartments) still to feel crowded.

I expect chaotic scenes in railway stations, and trains upon which I am unable to buy the basics – such as water.

I expect to get on very well with the other writers, to talk intimately, and, by the end, to overestimate the longevity of our developed friendships.

I expect students with very bad skin.

I expect questions about the state of contemporary British Fiction.

I expect to feel shamefaced about the ignorance displayed by my answers to questions about the state of contemporary British Fiction.

I expect to develop a crush on someone, probably our translator, if she is female. I expect, also, to resent being dependent upon the translator and having to compete for her time; this may develop either from or into a crush.

I expect brown-air pollution, political banners, newspaper walls, mopeds, guided tours, regional dishes, TV aerials, Canton-pop on the radio, cultural despair, stalls selling Mao badges, monks with bowls, sad temples, buffalo, rice, rice wine, laughing officials, eager young people, delays, inexplicable protocols, diarrhoea, vomiting, green fields, and tiny details that remind me surprisingly of England.

I expect to learn about five new words a day.

I expect Beijing to be nothing like I described it in Adventures in Capitalism, my first book: ‘Televisions. Smiling faces eating rice. Wide pale streets full of people riding bicycles.’

I expect men gambling, loudly; squatting.

I expect to feel, vis-à-vis Capitalism, a bit like an ex-junkie feels when surrounded by smackheads. With drugs, though, one can probably say ‘It’s a stage I needed to go through, perhaps it’s a stage you need to go through, too.’ With Capitalism, with China, the stage is one of the largest events in world history – it is end-possible.

I expect to be amazed I’m really here and this is part of the same earth I have always lived upon.

I expect to hate myself for being a tourist, to hate myself for not being able not to hate myself for being a tourist, and to spend much of my time hating that I spend so much of my time hating myself.

I expect to wonder whether the mistake I’m making is trying to understand it all. I’ve generally found travel writing bogus: I’d already taken on board the lessons of the uncertainty principle before I’d read very much of it. What have I read? All Chatwin; Robert Byron’s Road to Oxiania (as worshipped, and introduced, by Chatwin); Paul Theroux’s Riding the Iron Rooster (completely disappeared from my mind: not a single image left), and not a whole lot else.

I expect, in Beijing, shops not entirely dissimilar to those in London selling ‘traditional Chinese medicine’; I also expect shops entirely dissimilar to those in London, the purpose of which never becomes entirely clear, however much I ask.

I expect to see elderly women scuttling off down narrow alleys between fences in the twilight, wearing straw hats.

I expect to find much of the architecture disgusting and banal and gloom-inducing (Why did they knock down the lovely buildings that were here before? Why did they concrete the fields?), just as I do back in England, but to an even greater extent.

I expect steam, rising, and, seen through the rising steam, smiles on nodding faces.

I expect to have felt overwhelmed, embattled, defeated, exultant.

Interlude

Ideally, I expect would be printed on the left hand page and I remember on the right. The reader could then glance directly from one to the other, seeing where expectations were fulfilled and where memories were influenced by expectations. In the current arrangement, the reader’s own memory will be necessary.

I remember

I remember the first wish to stay in China forever and the first pulse of homesickness.

I remember feeling nauseous with the number of new memories I had acquired.

I remember not being able to write fast enough to record all the things that had happened or were happening.

I remember not wanting to take photographs because I felt my job was to turn my experience into memorable words.

I remember not remembering England as much as I’d expected to.

I remember not being able to remember what being bored was like.

I remember wishing I could record everything I saw, then realizing that with a camera crew, a photographer and seven other writers I probably didn’t need to.

I remember being certain I’d be able to tell one train journey from another, in retrospect, but now wish I’d taken a simple photo of each dining car.

I remember thinking that China was all brown as we traveled from Shanghai to Beijing and then changing my mind the further we went – China was also red (earth), orange (earth at sunset), yellow (crops), green (so much of it but most of all the Yangtze lit up by Chongqing neon), blue (sky and lake), indigo (sky at night), violet (sky just before night); mostly green and brown, though.

I remember, yes, I confess, I do remember singing my Elvis-version of ‘Unchained Melody’ during a karaoke session on a Yangtze riverboat.

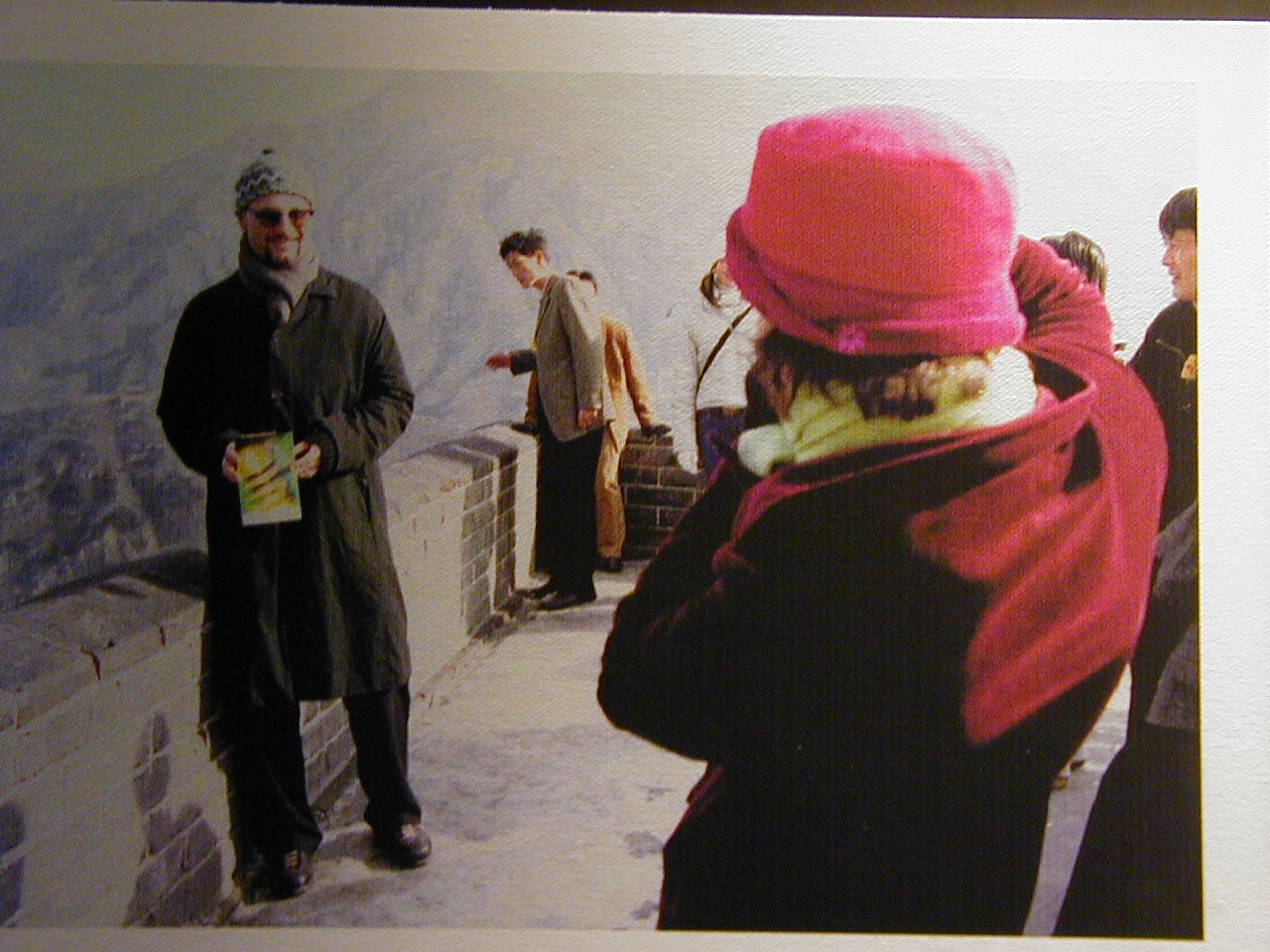

I remember climbing the Great Wall with Susan Elderkin, each of us saying, ‘We’ll just go to the next watchtower’ and then again ‘We’ll just go to the next one’.

I remember the sounds of the trains: the low growl of power that ran below everything, the rhythmic ker-chhk ker-chhk ker-chhk of the wheels crossing the sleepers (like a corrugated iron door slamming again and again – perhaps in Chinese zhege nege zhege nege), the almost-silence when we came to a complete standstill, the explosive shunt as we started up again, the little creaks and ticks from the roof, the jingle of the car-attendant’s keys as they strode along the corridor, the laughter from other compartments that always made me wonder what or who was being talked about.

I remember having dragons and demons explained to me during the tour of the Forbidden City.

I remember the inspection of the Guards in the Dining Car, after they’d had lunch – how they lined up in-between the banquettes before trooping off back to their assigned carriages.

I remember rabbits’ skulls glistening on street stalls in late-night Chongqing.

I remember the ‘Sightseeing Tunnel’ in Shanghai – one of the most truly psychedelic things I’ve ever seen; like the Alice in Wonderland ride from Blackpool Pleasure Beach redone for the 21st Century.

I remember aubergine with pork (I think all the British writers do) served us by waitresses on rollerskates at the Red Chicken in Shanghai.

I remember writing my first ediary in the company of one camera crew of three people, one photographer and Romesh Gunesekera in the bunk above writing in his notebook that he was being filmed by one camera crew, photographed by one photographer and sitting in the bunk above me, writing my ediary.

I remember the train-canteen kitchen filling with thick smoke and the Chef emerging only to wave his hand in front of his face and take another puff on his cigarette.

I remember, since coming back, my cravings for Chinese food which are, in disguise, my craving for China – a craving I can only compare to my ten-year’s sorrow at no longer living in Prague.

I remember spending over 100 hours on trains but it seeming almost as soon as it ended like less than a day.

I remember getting off the train at stations where we stopped for more than a couple of minutes, just to touch the still ground, albeit concrete.

I remember the young and enthusiastic hands being held out for my card after my talk at the British Council in Chongqing.

I remember my guilt and embarrassment at not having read The Dream of Red Chambers.

I remember trying to explain myself to people who had no idea who I was, and in the process having to explain myself to myself.

I remember the boy at Kunming no. 1 school who stumped me by asking, ‘What do you do with your day, except writing?’

I remember saying I had fallen in love with China in order to avoid giving another long detailed answer to the question of my impressions, and then realising it was true, that I had, and being disconcerted that I hadn’t realised this simple fact before.

I can’t remember if I’ve done enough I remembers.

I remember some of the other writers not being able to decide whether those were water buffalo or not, as the train took us towards Guangzhou.

I remember a fantastic view of something I’d never seen before cut off by the dark of a tunnel, and another fantastic view, and another tunnel, etc.

I remember feeling I was getting somewhere with the spoken Chinese language – that was before the decadence of Christmas.

I remember how distant and small the portrait of Chairman Mao seemed, at the top of Tiananmen Square.

I remember a literary magazine (Red Cliff Literature BiMonthly) which contained recruitment ads for the police force.

I remember the friendly tour guide telling us, ‘In Guangzhou we eat dogs and cats, but also McDonald’s…’

I remember the artist in Shanghai who covered his canvases with images made from the charred remains of books – and being told by him that his own house had burned down.

I remember how the Monkey-King at the touristy Beijing Opera reminded me so so much of Danny Kaye.

I remember feeling that the Chinese writers, despite them not speaking the same language as me, were essentially English and I remember also thinking I was only thinking this because I was too intellectually lazy to really start thinking quite how different they were.

I remember a line of five mops on a mop-rack in the toilets of the No. 1 School in Kunming.

I remember watching the flag-down ceremony on Tiananmen Square, and there being two young boys on their parents’ shoulders giving the Communist salute, and them being the only people in the whole crowd of two thousand to do so, but that being the photo I took.

I remember the brass floors of the elevators in the Peace Hotel, Shanghai.

I remember listening to a tape I’d made of songs about trains, most of them by American musicians, and wondering whether there were any good ones by British musicians (apart from ‘Rock Island Line’).

I remember seeing (from the train) the wheat harvesting done by hand, not even a horse and cart to help bring it in.

I remember miles and miles and miles – factories interspersed with fields and fields interspersed with factories.

I remember the smiling face of the girl behind the shop-counter at the Zen temple in Kunming as she told me, or so I thought, that I looked like Buddha.

I remember the laughs of the writers: Sinéad Morrissey’s unvindictive cackle, Ye Yanbin’s louder yack, Zhang Mei’s titters, Suse’s yuck-yuck, Zheng Zhe’s explosive ha!, Chen Dan Yan’s slight ascending and descending whimfle, Romesh’s rolling burr.

I remember Sinéad standing at a traffic intersection in Kunming, aurally deafening and visually overloaded, saying, every word definite, ‘This is. The People’s. Republic. Of China.’