When I was at university, somebody — a student rather than a tutor — told me excitedly that the third-person omniscient narrator was dead, because God was dead.

I didn’t go into mourning.

I hadn’t been attached to either.

Some of the curriculum novels that I was most familiar with — 1984 by George Orwell and Persuasion by Jane Austen — were third-person, but stayed close to a single character. (Winston Smith and dear Anne Elliot.) I had yet to read a Bleak House or a War and Peace.

My most shameful piece of cramming ever was getting through a tutorial on George Eliot having only skimmed the York Notes to Middlemarch. They were, I promise, the only York Notes I ever bought.

I read Middlemarch years later, when Leigh insisted it was my biggest gap. A while after we got together, we swapped firm recommendations. You have to read this, or I’ll always think you’re weird. I’ve asked just now. Neither of us can remember what I asked her to read.

Middlemarch, first hand, was astonishing. Everything in it is so very well put. And the third-person has complete social aplomb. These characters are all of them knowable.

And so, for quite a long time after university, I assumed writing omnisciently was a no-no.

It was only when I reached my eighth book, Hospital, that I challenged that.

The god-killing student’s logic, which I read about elsewhere, in books of literary theory, was that no-one — no kind of narrating entity — could assume that kind of third-person all-seeing all-hearing knowledge of other entities.

Because no-thing occupied that position, that mic’d up panopticon, no-one should write as if they did.

A conventional third-person omniscient novel is one in which a (Christian) godlike narrator is able to see into the heads and hearts of all the characters, and to travel at will backwards but more importantly forwards through time.

A paragraph that only an omniscient narrator could write is —

Little did Amelia know, as she was walking up the stairs built fifty years earlier by her grandfather, out of hardwood her great-grandmother had imported from her estate in Burma, that the woman she was about to meet — Katherine Banks-Watson — would become her greatest enemy and yet, in the end, after years of animosity, her most trusted confidante. Amelia was thinking only Clarence, the old family servant who she had encountered in the hallway, when he took charge of her suitcases. And Clarence, in turn, was meanwhile remembering — as he rode upwards in the lift to the Blue Suite in the Eastern Tower — the time Amelia had last entered the mansion, and all the trouble she had caused then. He was sure the same would happen again. But Katherine, turning away from the mantelpiece where she had hidden the love note from Alfredo within a tea caddy, had no such fear. For her part, all she could think about was Amelia’s money, and how most directly to get hold of it.

This is a very free and forgiving form of narration. But who would write this now, unless as a nineteenth century pastiche, for a bit of fun?

In trying to come up with an example, I’ve swayed towards an outdated idiom. Because even the transitions, the meanwhiles and the for her parts, seem old-fashioned.

Within this little triangular scene, the reader is being force-fed information. They are being fattened up with narrative calories. This is flagrantly tell, don’t show.

Most of all, it’s that leap with absolute certainty into the future — Little did she know — that seems questionable.

I can tell you this because I have already seen it all, because I made it up.

As in Walter Scott’s historical novels, such foreshadowing works best when the events being narrated happened a lifetime or a couple of generations ago. That gives them time to have become familiar.

It’s perfectly legitimate for me to say of my grandmother, Little did Muriel know on her wedding day that although she would be married a quarter of a century, she would be a widow for over fifty years.

Because of the time that’s passed, that’s sad and certain information available to me.

The same goes for any narrator who has decided to sing us those twentieth century blues. Events done and dusted can be thoroughly known. One can speak more conclusively of concluded lives.

Assuming this kind of authority when the would become of a future relationship takes us close to 2050 — that seems much more tricky. Will there even be a 2050?

Yet omniscient third-person narrators also want to jog alongside contemporary action, with that tone of Look at what they’re doing now — isn’t their ignorance marvellous!

Yet it’s possible for a narrator to take on the ability to head-jump without ever moving out of a limited and ongoing present moment.

He looks at her unaware that she already knows about his little secret.

In my own writing, and in reading that of students, I’ve noticed other things that are awkward about this supposedly freest and most powerful of all POVs.

Contemporary writers often experience difficulties in coming up with a smooth way of jumping from head to head (as Tolstoy goes from Anna Karenina’s thoughts to those of a minor character).

To address this, it’s often useful for the writer to settle on a general logic for when these switches occur.

For example, I will switch to a character when they are the person within the scene whose reaction it is most important for the reader to know, or whose emotions are likely to be most powerful, or who simply has the best eye-line for what is about to happen.

If you are really really confident about taking on this flitting point of view, and don’t overthink it — perhaps hardly think about it at all — that will help a great deal.

I’m going to go where the action is, and cut to it whenever the moment takes my fancy — even mid-sentence.

That’s legitimate, that’s the spirit — as long as you’re not hung up on the lingering god-thing.

The moment you start to lose the bravado of charging into an unknown character’s head, and riffling through their secret thoughts, you’re in trouble.

A contemporary third-person omniscient novelist needs to be reckless, and particularly not to care about questions of who has the right assume they can look into other people’s minds?

AS IF can hang over the door of such an enterprise.

I’m writing all of this intimacy and social scoping and scooping AS IF I could do it, which of course I can’t, but I’m going to give it my best go.

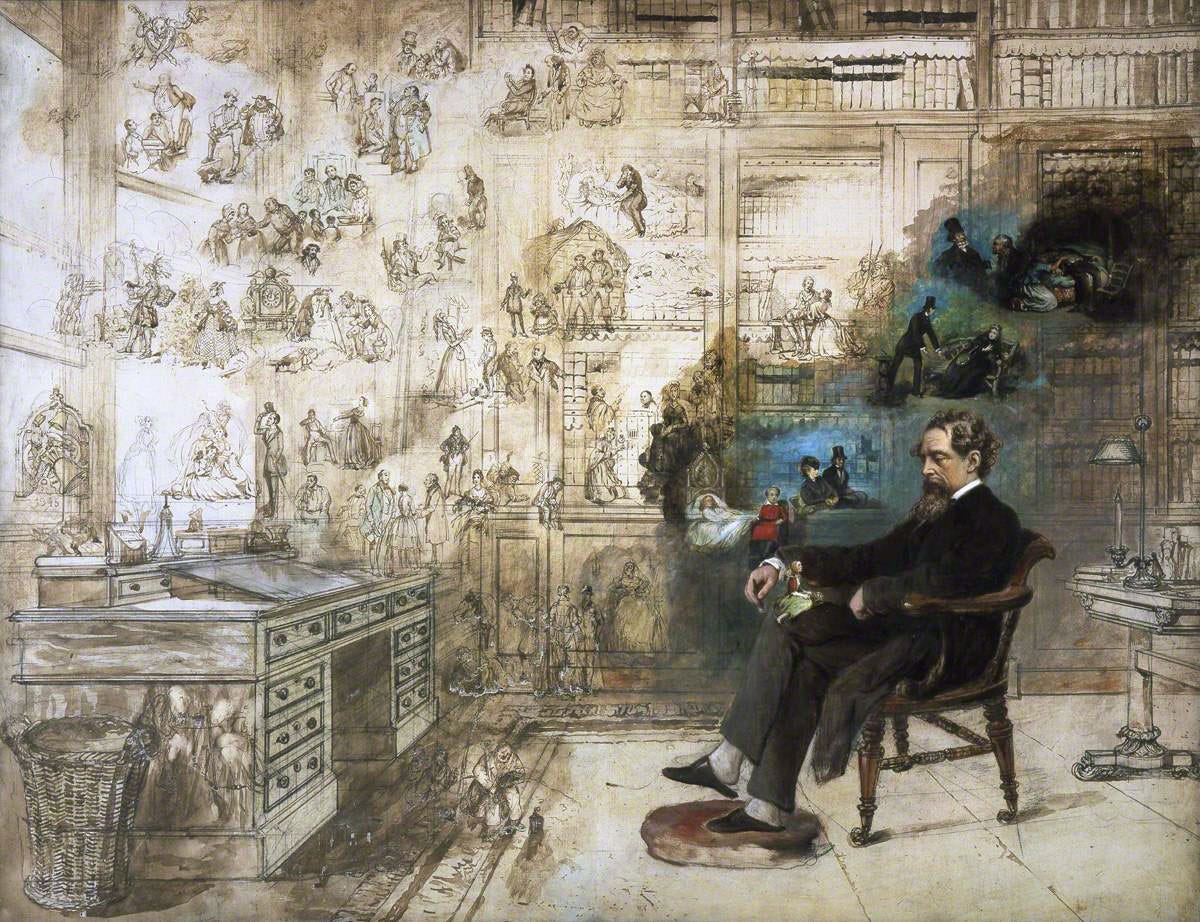

Look at me with my proud eyes and ears and teleportation device and telepathic powers and time machine — I am going to do transitions as insanely confident as Dicken’s famous one in Bleak House. Let’s hitch a ride on a POV-bird.

The day is closing in and the gas is lighted, but is not yet fully effective, for it is not quite dark. Mr. Snagsby standing at his shop-door looking up at the clouds sees a crow who is out late skim westward over the slice of sky belonging to Cook’s Court. The crow flies straight across Chancery Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Garden into Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Here, in a large house, formerly a house of state, lives Mr. Tulkinghorn. It is let off in sets of chambers now, and in those shrunken fragments of its greatness, lawyers lie like maggots in nuts. But its roomy staircases, passages, and antechambers still remain; and even its painted ceilings, where Allegory, in Roman helmet and celestial linen, sprawls among balustrades and pillars, flowers, clouds, and big-legged boys, and makes the head ache — as would seem to be Allegory’s object always, more or less. Here, among his many boxes labelled with transcendent names, lives Mr. Tulkinghorn, when not speechlessly at home in country-houses where the great ones of the earth are bored to death. Here he is to-day, quiet at his table. An oyster of the old school whom nobody can open.

I goes where I likes, I does.

I did enjoy this - thanks, Toby! I think there's an important distinction - important for the writer, that is - to be made between the truly omniscient narrator, which feels weird to us C20 and C21 creatures aware of the limits of any human's knowledge and wisdom, and what A S Byatt calls a 'knowledgeable' narrator. The latter feels much more natural to me: a narrator who does see into more heads than one, and knows more than any single character can know, but not necessarily a god-like everything and everywhere. I find the best analogy in the swipe-card that big companies and universities issue: the writer choses what access the narrator has, and what it doesn't, and codes their swipecard accordingly - then has a series of decisions, through about where the narrator is at any one point.

My fondest reading experience with third person narration is in Gravity’s Rainbow, most memorably in part one in an episode that moves from Jessica to Roger to Pointsman and back again in reverse. The narration feels unmoored, not omniscient, like it’s hallucinating the thoughts and feelings of the current character it isn’t so much observing as it is being possessed by. The narrator looks outward from within the psyche of the current host, not inward from a deified aloofness. The narrator is something like the novel’s Pirate Prentice character, then, caught up in someone else’s fantasies. It contributes to the difficulty of the novel. A seasickness can creep in after so many and so frequent shifts of perspective, but I like the challenge, the hard cuts. Moviegoers must have felt this challenge when multiple perspective camerawork became a thing.