Whilst I was in Paris, I went to the Musée Rodin.

I have wanted to go for years.

It was even more amazing than I had expected.

Since getting back home, I have been reading again Rainer Maria Rilke’s ‘The Rodin-Book’ of 1903 and 1907 — translated by William Tucker and published by Quartet Books in 1986.

Along with David Sylvester’s Interviews with Francis Bacon, Osip Mandelstam’s ‘Conversation about Dante’, and Virginia Woolf’s Diaries, this is one of my sacred texts.

In one extraordinary paragraph, Rilke defines how — in his view — Rodin’s great originality came into being.

Rilke has been going through Rodin’s drawings by type — wash drawing, figure drawing, illustrations, drypoint etchings.

All of which, more generally, is saying that artists learn by being protean, by passing from shape to shape, means to means.

Finally, there are those strange documents of what is momentary, of what is almost imperceptible as it passes. Rodin had the theory that if insignificant moments of the model, when he believed himself to be unobserved, were caught rapidly, they would give a vividness of expression of which we have no idea because we are not accustomed to follow them with keen, alert attention. Keeping his eye constantly on the model and leaving the paper entirely to his experienced and rapid hand, he drew an immense number of movements which till then had been neither seen nor recorded, and it turned out that they had a vitality of expression which was tremendous; associations of movement appeared which had hitherto been overlooked and unrecognized, and they possessed all the directness, force, and warmth of pure animal life. A brush of ochre passed with varying pressure rapidly over the outline produced in the enclosed surface such an incredibly strong effect of modelling that one seemed to have before one plastic figures of baked clay. And once again a whole new vista filled with nameless life had been discovered; deep places, over which all others had passed with echoing steps, yielded their waters to him in whose hands the willow-rod had prophesied.

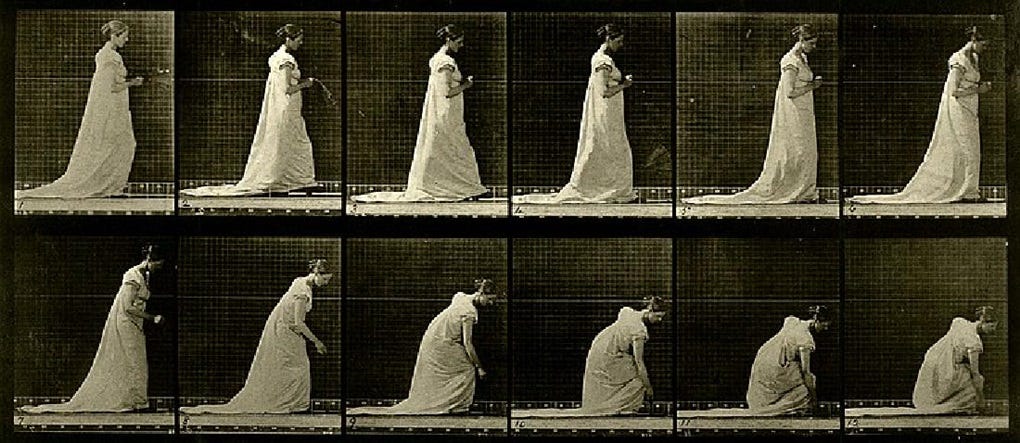

Rilke is describing Rodin as if he were Eadweard Muybridge.

But Muybridge had cameras to do his momentary recordings; Rodin was by himself.

This is Rilke’s assertion.

Rodin’s drawings, and his subsequent sculptures, had originality (associations of movement… which had hitherto been… unrecognized) but also veracity (all the directness, force, and warmth of pure animal life). They were — along with Michelangelo, and the Greek sculptors — among the truest, most vivid, representations of women and men.

And how did this come about? Rilke’s description is definitive.

The artist, separated into hand and eye, has such an experienced hand — developed through years of rapid drawing — that they need no longer look at it or at the lines produced by it as they work. Instead, all their sight and sensitivity can go into exploring the briefer and briefer moments they are therefore freed up to be able to perceive.

This, it seems to me, applies not only to drawing but to writing, playing music, sport, and to all forms of hopefully original making.

It explains why it is worthwhile doing over and over again whatever, in those separate forms of expression, equates to sketching.

For a writer, this is note-taking, is redrafting sentences, is reading with pencil in hand.

There are no short cuts.

But once the rapidity of the hand (or hand equivalent) has been developed, the time of the seeing opens up.

I find this totally convincing, because it explains why originality of vision only gradually becomes available after many hours of looking-noting, and why those hours of looking-noting are never wasted.

Rilke compares this to dowsing, to finding underground water through being attuned, and having the simple means — twigs! —

An artist sees what is almost imperceptible as it passes. And art becomes possible in that almost.

Those moments are constantly happening, all around us, on every stuck-in-traffic bus journey, at every supposedly-dull party.

We just need to make ourselves quick enough to see them, recognise them, catch them.

And your post help emphasise why editing is so important too.

I like dowsing as analogy. Also, alchemy. Taking the base elements and transforming to gold.