On Shorter Books

by Claire Keegan, Max Porter and Others

Claire Keegan is the writer of the moment. Both Foster and Small Things Like These are not just bestsellers but phenomenal bestsellers.

I’d define these as books that sell better than books sell. Because they become obligations (everyone else has read it) or gifts (mum’ll love it).

With this success, Claire Keegan, and Faber Books, may be changing publishing.

For the better, in lots of ways.

I always used to feel guilty that a Creative Writing dissertation, 15,000 words for MA or 40,000 words for MFA, was a useless kind of length.

If a student writer wrote something wonderful that was complete, but fell in between those two wordcounts, they would still end up with something hopelessly unpublishable.

It would be a too-long short story, or a too-short novel, or something that was neither.

What we heard from publishers were assertions that novels generally had to be 70,000 words or more. Otherwise the readers felt swizzed.

A literary magazine, such as Granta or the New Yorker, clearing enough page space to feature a 15,000 word story by a debut writer was — I’d guess — a once-in-a-decade event. (A version of Foster appeared in the New Yorker (2010); Keegan was well established.)

Editors of online magazines would assume that only a very small number of readers would get to the end of such an extended screen-scroll.

And because of this, if agents took on our graduating students they generally encouraged them to extend their novellas into full-length novels, or integrate their overlong stories into short story collections.

Perhaps, thanks to Claire Keegan, these oddities and awkwardnesses will now get more of a chance.

Much of publishing, in relation to book length, is a matter of status — the established status of the author, or of the editor.

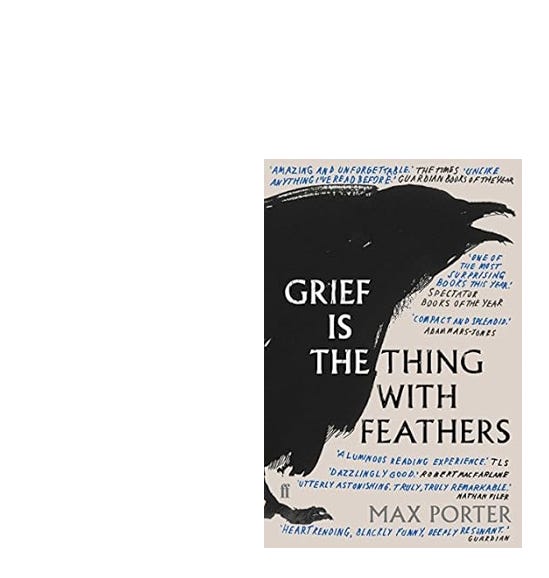

I’d say that the origin of Foster (2021), and why it was accepted as being long enough for a book, and how it is physically presented, lies in Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers (2015), also published by Faber.

Put the two books alongside one another, and they have the exact same formatting. Flaps, embossed lettering on the cover. Both were printed by CPI Group, Croydon. Both (despite inflation) sell for £8.99 — and both have found a readership pleased to pay much that for an hour or an hour and a half’s entertainment.

Faber have a history of publishing full price books containing a small number of words, and a large amount of white space.

Several of their poetry collections, including Sylvia Plath: Poems Selected by Ted Hughes and Emily Dickinson, also selected by Ted Hughes, both 80 pages, were notoriously slender.

I remember Private Eye noting this. Perhaps someone out there knows the costliest book, per word? (There are works made up of entirely blank pages, I know.)

Going back to the issue of literary status, Max Porter brought a great deal of this with him. He was a brilliant and established editor at Granta/Portobello Books. His own editor at Faber saw that Grief is the Thing with Feathers wouldn’t benefit from building up or bulking out. A chance was taken, and it paid off.

Max Porter talked about this in an interview with the Guardian —

The fact is that, had he not been able to place it directly into the right editor’s hands, it might well not have seen the light of day at all. “The first person I sent it to was a publisher friend, and she said exactly what I expected: ‘It’s good, but I don’t know what you could do with it.’ But Faber liked it, and saw a way of publishing it, and I’m hugely grateful.”

The spacious text design of both Grief and Foster — wide margins, large font — visually conveys to the reader that they are reading prose of high quality (which they are).

This means, I think, that readers read more respectfully and carefully. They are partly thinking of the space around poems, and the weight of a sentence that is not being vertically crushed between other sentences.

Samuel Beckett, published by Editions de Minuit and John Calder, insisted on bigger and bigger fonts for his shorter and shorter later works. Look at Imagination Dead Imagine or Worstward Ho. When these texts are reprinted in editions such as I Can't Go on, I'll Go on by Grove Press, or Nohow On by Calder, they are literally diminished — smaller letters, smaller achievement.

Beckett, by the time of his death, had the highest literary status of any author. He could put out special editions of extremely short texts, as whole books, in order to help his publishers out of financial difficulties. No-one complained about being swizzed. They were bought as collectibles, and their value has increased.

Claire Keegan’s books bring a sense of occasion to the page — augmented by the film adaptations, The Quiet Girl (2022) and Small Things Like These (2024).

A story that deserves a movie is always seen as a better story — especially when it’s a really good movie.

And short stories often adapt better to 90 screen minutes than long, complex novels.

All of which means that the very long short story and the shorter novella may be written with slightly greater chance of publication than they were a decade ago.

They are no longer hopeless forms.

Eliot added his notes to the Waste Land as the publisher felt it was too slight to stand alone.

I never understood how this stupid idea a novel had to be 70K words minimum started. In the first half of the 20th century, there were untold classics of 30-50k words. The idea word count equals value is an idiot's belief. I see more value in 30-50K words of exquisite genius, than 70- 130K words of mediocre padding and standard work.