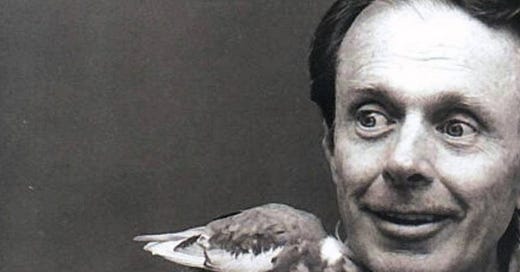

I once saw Hubert Selby Jr. in the Royal Festival Hall.

He did a reading and a Q&A.

I was not close; maybe fifteen rows back.

He was small, ill, old, fierce.

When asked about self-censorship, he said he didn’t self-censor.

He said —

If it comes in the brain, it goes on the page.

And I wrote that down, and took it as an ethic.

From the writer of The Room (1971) and Requiem for a Dream (1978).

Which means that, over the years, in diaries and even more in notebooks, I have written down what would be — were anyone to read them — appalling and shameful things.

But I know that I have not followed Hubert Selby Jr (who is not at all among my favourite writers; I didn’t even finish Last Exit to Brooklyn — I should) —

I have not followed this ethic perfectly.

I know there are things I’ve thought but did not write.

Increasingly so, in recent years.

At one stage, I believed someone apart from me, after me, might be academically interested in my unpublished writings. They might even read through all my notebooks.

I think that vanity has gone.

But I am aware that a single sentence can destroy a reputation, and I’m pretty sure — somewhere — I’ve written that sentence. Several times.

Who isn’t vengeful or hateful? Who doesn’t sometimes try to turn words into wounds — if only imaginary wounds? Who lacks a subconscious, or pretends they can control their subconscious?

When I write, it’s not always as myself. Sometimes what comes through is a possible thought a possible character might have. In which case, I’ll usually put inverted commas around the sentence — to show that it’s fictional.

That it’s not me there.

At other times, if I know the words might be the start of something made up, I will write novel next to them, or s/s for short story.

This is defensive, and wouldn’t mean anything to someone — a police person — going through the notebooks for evidence of thoughtcrime.

They’re my notebooks.

A writer of fiction can have the words of one of their fictional characters quoted against them, as if it were him or her or them who said it.

They can have their private utterances turned into T-shirt slogans they wore on live TV.

Because the mere words are the only necessary proof.

Unlike most people, writers — if they’ve put down a sequence of letters expressing a certain sentiment — can’t deny that that thought went through their head.

It only ends up on the page if it’s gone through the brain.

Is this your handwriting? says the prosecuting lawyer.

Yes, but — says the writer in the dock.

You are not denying this is your handwriting?

No, but — if I can explain

No further questions, your honour.

And so, increasingly, I’m aware that I am more likely than not to self-censor.

I am interested to know if you feel this way, too?

If so, do you think this has a hindering effect on what you write afterwards.

My understanding of Hubert Selby Jr.’s statement, at time time and still today, is that there is a continual flow of utterance, and that to interrupt it is dangerous.

At the very least, you should put down what has come up — have it out so you can estimate it.

It’s another version of the variously quoted —

How can I know what I think till I see what I say?

How can I know what a possible character might think and do and be until I give that character a chance to come into existence?

But who — which writer — would now risk saying, Self-censorship is dangerous? Self-censorship is not only psychologically but culturally unhealthy?

What happens in the brain, stays in the brain.

After reading through notebooks that I wrote during very dark periods of my life, I threw them out. I was afraid someone would see them and I was embarrassed by how dark and hopeless they were. Now, I regret doing that because I might’ve been able to use some of that for a character.