On Reading Other Writers' Drafts

'Leftie crap,' he said, then walked away.

Any writer will learn a vast amount by looking closely at another writer’s drafts.

Not least, they can pick up their private language of signs. How they delete, highlight, interpolate and shift chunks from there to here.

This isn’t a given. At middle school, I was taught how to cross out. Don’t scribble or do loops. Just pass single horizontal line through the heart of the letters, to kill them — and my line was never straight enough, not even when I tried a ruler.

But I picked up much of the rest of how a fluid, in progress manuscript should or can look from T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land: A Facsimile & Transcript of the Original Drafts. A copy of this was in the school library.

One afternoon, when I had a free period, I was sitting in a chair between two bookstacks, reading this big blue book. The Physics Master, who was reputed to have once been on a plane overflying a nuclear bomb test, came up behind me.

‘Poetry, Litt?’ he asked.

I turned round, not a little unnerved.

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

The Physics Master paused, then said, ‘My daughter writes poetry.’

I paused. This, I thought, was an unprecedented moment of intimacy. But how could I respond.

‘Really?’ I said.

He breathed in.

‘Leftie crap,’ he said, then walked away.

If I hadn’t loved Eliot already, that would have done the job.

The Physics Master’s catchphrase, when setting homework, was to say, ‘Read, learn and inwardly digest pages X to Y of your textbook.’

That, I suppose, was what I was doing with Eliot. (Like Auden said of Yeats, ‘the words of a dead man/ Are modified in the guts of the living.’) But it wasn’t just Eliot — also putting their notes into his typescript were Ezra Pound (‘make up yr mind you Tireseas if you know known damn well or else dont’) and Valerie Eliot (adding ‘What you get married for if you dont want to have children’).

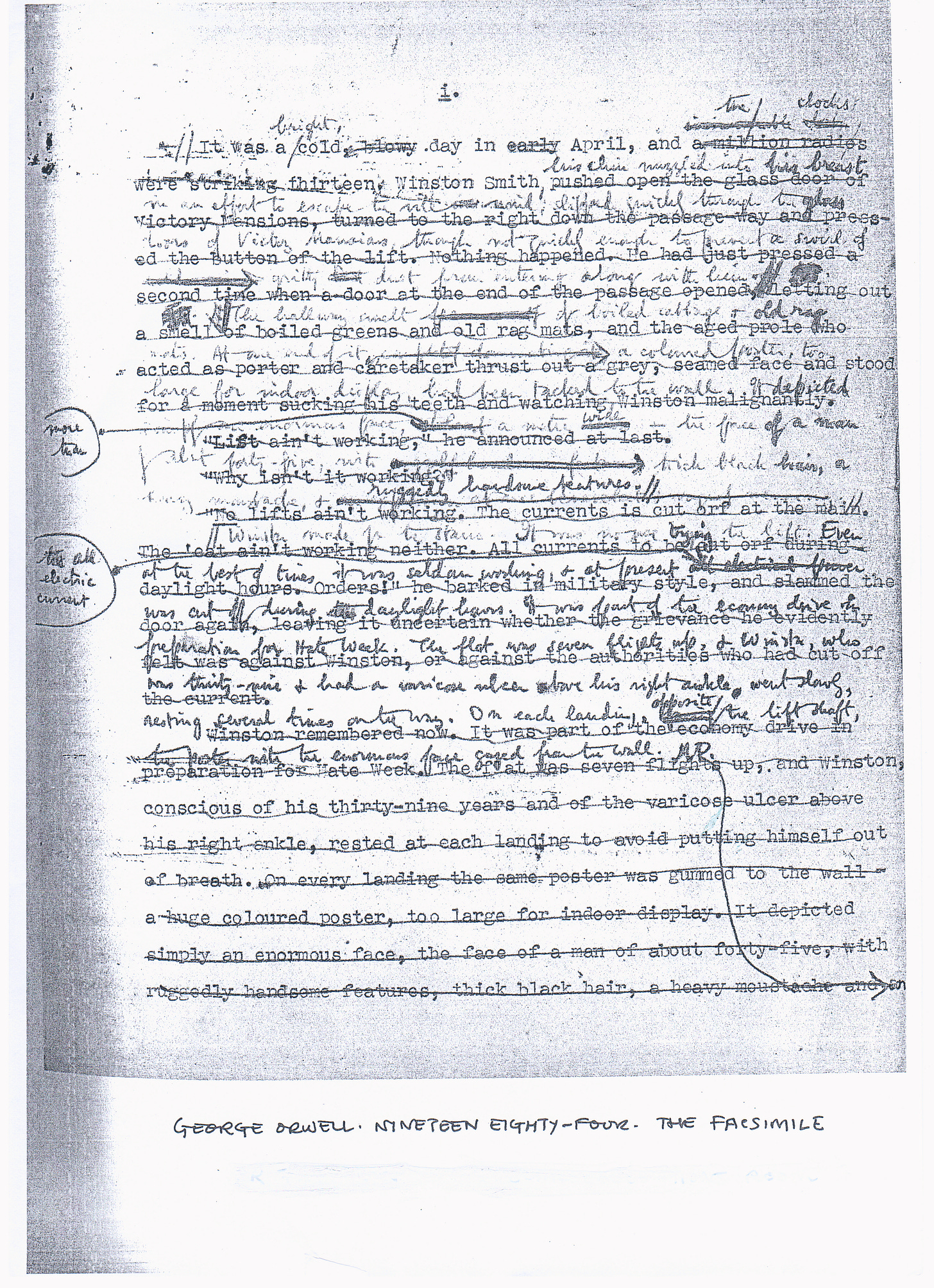

Later, at university, I found my way to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: The Facsimile of the Extant Manuscript. This amazed me. Orwell had typed up the whole novel, then seemed to have been dissatisfied with every single sentence.

I saw how much rewriting some writers did. And then, with Jane Austen’s Sanditon, and Henry James’s The Europeans, I saw how much rewriting some writers absolutely didn’t do.

The best source of single pages of manuscript are the Paris Review Interviews. But here, I think, some writers asked to share a sample of their work-in-progress swank or clam up. They either put up something very heavily rewritten, to give the impression they are Flaubert on a bad year, or they share something almost untouched, so as to keep their trade secrets. In every case, there are clues. Neat handwriting or scribble? Typewriter or word processor?

Many manuscripts and typescripts are available online. Here’s David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King, the first page of JG Ballard’s Crash, some of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, and Franz Kafka’s The Trial.

What’s most important is to witness the production of sentences as messy, momentary. My favourite description of writing is from Edgar Allan Poe in ‘The Philosophy of Composition’:

Most writers—poets in especial—prefer having it understood that they compose by a species of fine frenzy—an ecstatic intuition—and would positively shudder at letting the public take a peep behind the scenes, at the elaborate and vacillating crudities of thought—at the true purposes seized only at the last moment—at the innumerable glimpses of idea that arrived not at the maturity of full view—at the fully-matured fancies discarded in despair as unmanageable—at the cautious selections and rejections—at the painful erasures and interpolations—in a word, at the wheels and pinions—the tackle for scene-shifting—the step-ladders, and demon-traps—the cock’s feathers, the red paint and the black patches, which, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, constitute the properties of the literary histrio.