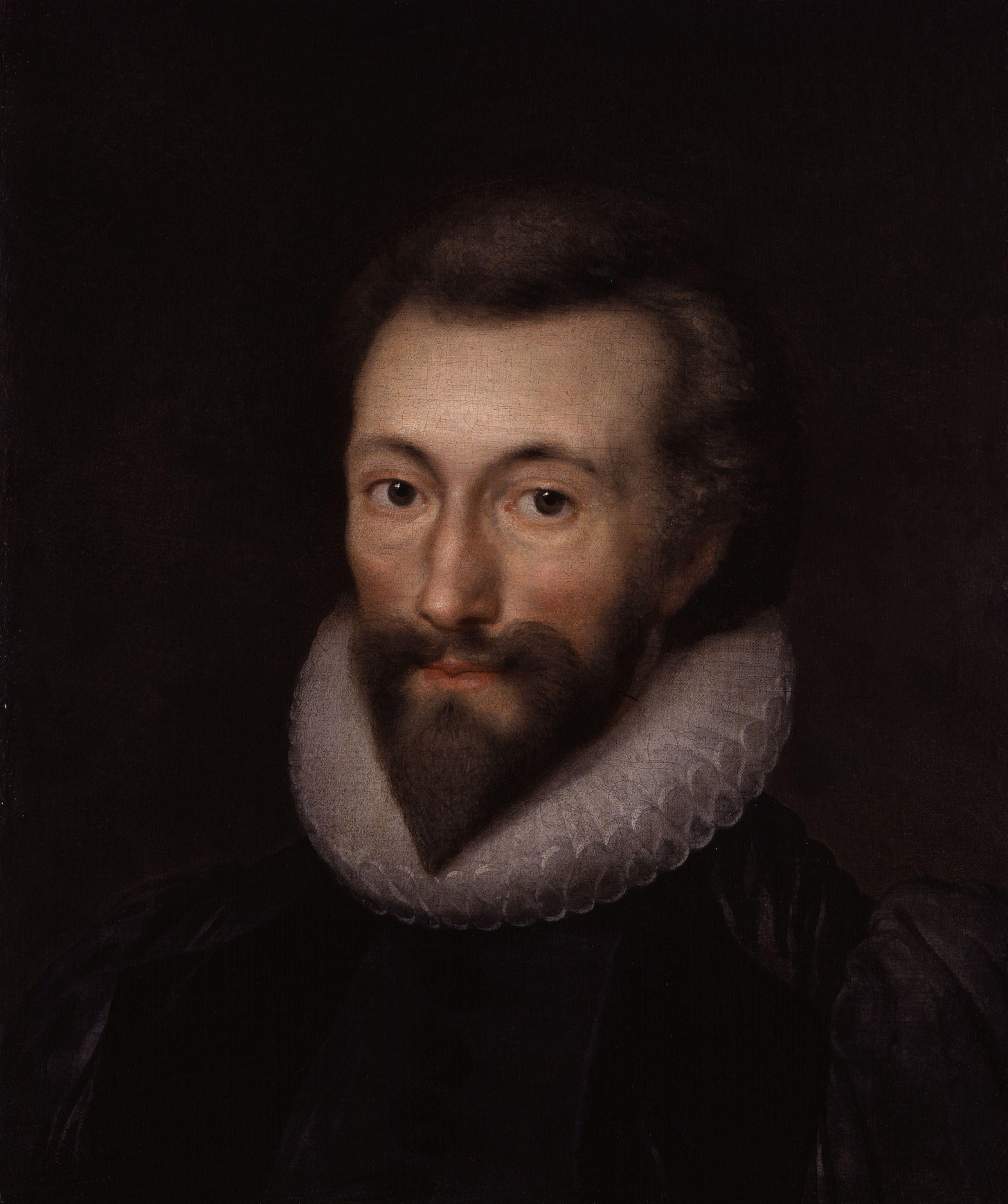

In 2017, I was asked to write a close reading of this poem by John Donne, for The British Library website — to be used by GCSE or ‘A’ Level students.

This was a lovely commission. Donne is a poet I read very often. And I gratefully remember John Carey’s lectures on him from my time at university. Carey, thin, indefatigable, witty in his tight black leather jacket.

A couple of days ago I found out that, because of the cyber attack, the falling star piece hasn’t been available on the BL site for a while.

However, I know that some teachers and university lecturers have it on their reading lists. So I’m reposting it here, with a downloadable pdf of the text at the bottom, to provide a temporary replacement — until the British Library site is running again.

I hope it’s interesting to other readers. It’s important to emphasise that all writers are living creatures, still addressing us, not dead texts recording dead thoughts.

“TIME AND SPACE IN DONNE”

Let me start with something that could not be more obvious. When he wrote his song ‘Goe, and catche a falling starre’, John Donne was alive.

I don’t mean that as a poet he was most completely alive when writing poetry, though that’s probably true.

What I mean is far more basic: that a man called John Donne was a living, breathing, changing, reacting being when he dipped his quill into an inkpot and first wrote these lines – lines we can read over three hundred years later.

It is possible Donne had dreamed the poem up days or weeks before he wrote it down, and had thought of it occasionally to tinker with it as he walked or rode a horse or lay in bed, alone or not.

Yet at one point in its existence, the latest word he scratched onto the parchment was wetter and darker and less aborbed than those preceding it, and his breath coming warmly down helped begin drying that word.

Books are dead, and words are inanimate, but they were livingly written.

W.B.Yeats, in a poem called ‘The Scholars’, attacked those who forget this initial liveness of writing:

Bald heads forgetful of their sins,

Old, learned, respectable bald heads

Edit and annotate the lines

That young men, tossing on their beds,

Rhymed out in love’s despair

To flatter beauty’s ignorant ear.

And one of those despairing poets, John Keats, in a fragment written when he knew he was dying of tuberculosis, did his absolute best to destroy the possibility that the reader could forget how alive he had been whilst writing:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasp, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calmed – see here it is –

I hold it towards you.

This is one of the most amazing gestures in all English poetry – literally, a gesture; and Keats, as he traced these inky words, was both looking down at his living hand and taking his dying hand as the subject he wanted to immortalize. All Keats asks of his reader is to ‘see’ the hand, yet to do that is to do the impossible: to look through the words on the page and see the hand that only a moment – or two hundred years ago – wrote them.

Keats is not as bossy as Donne, who is an extraordinarily bossy presence. Donne just won’t stop telling the reader what to do, and the things he demands of them are equally as impossible as the one Keats demands:

Goe, and catche a falling starre,

Get with child a mandrake roote,

Tell me, where all past yeares are,

Or who cleft the Divels foot,

Teach me to hear Mermaides singing,

Or to keep off envies stinging,

And finde

What winde

Serves to advance an honest mind.

In Donne’s time, this would have been read as a list of folkish bywords for impossibility. Catching a falling star was like finding the gold at the end of the rainbow. Some of the lines, such as ‘who cleft the Divels foot’, refer to riddles. Another lyric poet, Robert Graves, claimed to have solved several of them in his book The White Goddess. They are also central to the plot of the fantasy novel Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones.

I began by reminding you, as I didn’t really need to, that Donne was alive when he wrote his poetry. I’m going to continue, equally unnecessarily, by reminding you that you are alive as you read it. These are the givens of the situation of a poem on the page seen by eyes looking down – as your eyes are looking across or down at this screen – at words in a language they understand pretty well (or, at least, thought they understood before they started reading poetry from over three hundred years ago). But these givens can very easily be covered up or ignored. If a poem says something like Byron’s

She walks in beauty like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

it doesn’t insist on anyone’s being alive, apart from the female subject; and she is so idealized as not really to exist as a real person – we just learn she is lovely and has very dark hair. Byron’s poem exists in a drifty, idealized time where the present tense of ‘She walks’ absolutely doesn’t mean ‘On Saturday 12th June 1814 at 3:35am, which is when I am writing about her’. The present tense means something more like ‘When she does walk, she can’t help but walking in beauty like the night’. This is a lot less clear than ‘She walks with a slight limp on the left side’ or ‘She walks slowly back from Tescos carrying two heavy plastic bags’. It also leaves the reader in no time at all. The most the poem does is say, ‘If you can apply these words to your own dark- haired beloved, feel free to do so.’ What it certainly doesn’t do is boss the reader about. It doesn’t say, ‘You, walk, now!’

Donne’s poem does:

Goe,...

If the poem ended here, the reader would have received a direct order, in the imperative, and would be left wondering where exactly the poet had meant them to ‘Goe,...’

Donne immediately establishes a living relationship between himself and the reader – even more living than the one Keats tries to create in asking the reader to ‘see’.

‘Goe,...’ doesn’t just demand engagement in the space the reader occupies, it commands movement away from that space. And the thing is, the living reader could obey – they could, because they are alive, go, in the moment that follows the order. But Donne is not just very bossy, he is also very mischievous. No sooner does he make a demand on the reader but then undoes it by making that demand impossible.

..and catche a falling starre,...

The comically super-obedient reader, halfway out the door, or mentally readying themselves for departure once they hear where they should go, is halted and a little humiliated.

In terms of space and time, what Donne orders the reader to do is very complicated. Think about it. To even try ‘to catche a falling starre...’ would require the reader to spend night after night looking up at clear, starry skies in hopes of seeing a falling starre to then hopelessly sprint off after.

This image reminds me of the American lyric poet Randall Jarrell’s definition, ‘A poet is a man who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times.’ (I’m aware that this definition starts ‘A poet is a man’ — and Donne, Keats and Yeats would all have made this masculine assumption. The writer is often figured as male, the reader as female. ‘Goe, and catch a falling starre,...’ is an exception. The reader is male.)

Donne’s next order also involves travel, and a lot more than travel:

Get with child a mandrake roote,

(This is a little like the legendary recipe that began ‘First, catch your hare...’) I won’t go into further detail here. ‘Get with child’ means impregnate.

For the next lines, the reader is expected to be back in the room with Donne, having completed the research and taking time out to

Tell me, where all past yeares are

Or who cleft the Divels foot

Then some kind of journey together, a sea voyage of poet and reader, is expected.

Teach me to heare Mermaides singing

The next demand is more like an emotionally needy request

Or to keep off envies stinging

We seem to be back in the same room with Donne, but the final lines take us out to sea again:

And finde

What winde

Serves to advance an honest Minde.

At least in anticipation, Donne is pinging his reader and himself around in time and space almost as frantically as Steven Moffat does Doctor Who.

In the second stanza, Donne acknowledges that only certain people, and he doesn’t know if the reader is one, would be capable of such impossibilities:

If thou beest borne to strange sights,

Things invisible to see,

Ride ten thousand daies and nights,

Till age snow white haires on thee,

Thou, when thou retorn’st, wilt tell mee

All strange wonders that befell thee,

And sweare

No where

Lives a woman true, and faire.

In comparison to the first stanza, this transforms the reader into a fairytale figure setting off on a magical quest (a male figure, a Handsome Prince, because a Beautiful Princess could not possibly be imagined to ride that far). 10,000 days is just over 27 years, so although it sounds very long it’s not beyond a human life-span.

Only in the final line of the second stanza do we arrive at the real subject of the poem – the question it has been aiming for all along. Is there a woman both true and fair? This is an entirely conventional question for Elizabethan love poetry.

In the third stanza, we reach the point I have been aiming for along — in emphasizing Donne’s aliveness as he wrote and your aliveness as you read. But first I need to mention my third really obvious thing: some poetry, including this poem of Donne’s, rhymes.

Now, there have probably always, in all cultures, been bards and rappers who could spontaneously compose verses, but they tend for simplicity’s sake to make these verses rhyme aa bb cc or aaaa bbbb. Donne’s rhyme scheme is ababccddd — probably within the capabilities of a really good rapper, but quite a stretch to do it three times in a row, and hit all the right beats.

In other words, there’s no way that this is an entirely spontaneous utterance. It has taken time to make the rhythm and the rhyme. I have been reading the poem as if Donne’s orders came out one after the other, just so. But they are clearly crafted. He has had at the very least a few minutes to change them. So why, in the third stanza, do we come to this moment? – in its way, I think, as amazing as Keats’s extended hand:

If thou findst one, let mee know,

Such a Pilgrimage were sweet;

Yet doe not, I would not go,...

The whole poem has been building energy, tending faster and faster towards a journey off to meet the woman true and fair. But Donne in three words says that even if such an impossible person exists, he isn’t bothered to meet her. Huh? What the – ?

Bathos is the technical term. But what I want to point out is that this is the moment where the poet, even in a crafted and rhyming poem, is most spontaneously alive. Because he changes his mind. With ‘such a Pilgrimage were sweet’ he’s packed and heading off to the Holy Land. With ‘I would not goe’, he’s sulking in his closet.

Though at next doore wee might meet,

Though shee were true, when you met her,

And last, till you write your letter,

Compare this to the balanced, image-heavy lines of the first stanza – it really wants to seem like the most offhand things a person could say. The lines are deliberately scrappy, not to say crappy; two in a row begin with ‘Though’, ‘meet’ is varied only as ‘met’. Every word is monosyllabic between ‘Pilgrimage’ and ‘letter’, and after that the rest of the poem is also desultory monosyllables. It also concludes by rhyming on ‘eee’, the easiest, laziest of all English rhymes, as every parent who’s heard their child compose an ‘Ode to Wee’ will know. The syntax is scrabbled, self-correcting:

Though shee were true, when you met her

is far less elegant than the obvious

Though when you met her shee were true

These are exactly the ‘harsh numbers and uncouth expression’ that Samuel Johnson disdained in Donne.

The harshness and uncouthness is deliberate. Having shown he can change his living mind, Donne now focusses on changing the moment by moment meaning of what he is saying, which we see from the few lines left must end very soon. He shifts his tone, becomes despairing, then sarcastic, then outrageously cynical.

Though she were true, when you met her,

And last, till you write your letter,

Yet shee

Will bee

Falfe, ere I come, to two, or three.

This isn’t unlike King Lear’s misogynistic accusation of lechery in womankind: ‘The fitchew, nor the soiled horse, goes to’t with a more riotous appetite. Down from the waist, they are centaurs, though women all above.’ (Act 4, Scene 6, Lines 119-121)

Donne’s living attitude has shifted, by the end of the poem, from haughty bossiness to cynical passivity. The reader has been given a dozen orders which they now know they weren’t ever expected to obey.

Although the mind-changing of the third stanza is exceptional, I’ve chosen ‘Song’ because it shows Donne as he usually is. He is always situating himself and his reader in both time and space. In ‘The good- morrow’ he and his lover are in bed, waking early in ‘one little roome’ after a night of pleasure. Rather than order the reader to go on impossible quests, Donne relishes our shared post-coital langour:

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, world on worlds have showne,

Let us possesse one world, each hath one, and is one.

In ‘Elegie XIX Going to Bed’ we are at the other end of the day, and are pre-coital:

Come, Madam, come...

(Not ‘Goe,...’)

..all rest my powers defie,

Until I labour, I in labour lie...

Bossy-boots Donne is back, but these orders are not for impossible quests, they are easily obeyable. ‘Off with that girdle... Unpin that spangled breastplate... Unlace yourself... Off with that happy busk... Now off with those shoes...’

The seduction continues, it seems, in real time. But Donne surprises us at the poem’s end, revealing this has all been persuasion, not description. The woman we are is still fully dressed, it is the poet who has stripped:

To teach thee, I am naked first

When we read Donne, he is always doing this, confronting the time and place more nakedly, but always within the conceit of rhythm and rhyme, and always with designs upon us.

Great to be reminded of the living poet. Thank you.