As an aside, before I start, I recently taught a creative writing workshop in a large library.

To help us get to know one another, I asked everyone in the group my new question. It’s not, Who is your all-time favourite writer? because that, I think, only tells you about the person as they are that day, and perhaps as they want to come across in front of literary types.

Instead, I ask, Who is the writer you have spent the longest amount of time reading, in your whole life?

This tends to send people back to their teenage and earlier reading.

Who is it for you?

(For myself, I think the answer is probably Jane Austen, because I studied Persuasion at school, and have read the other five novels plenty of times.)

Very often, especially when the group is youngish, the answer will be JK Rowling — followed by some kind of apology or moue of dismay.

But during the library writing workshop I got this unexpected answer —

J.K. Rowling, but only when she’s writing her crime books as, what is it? Robert Galbraith.

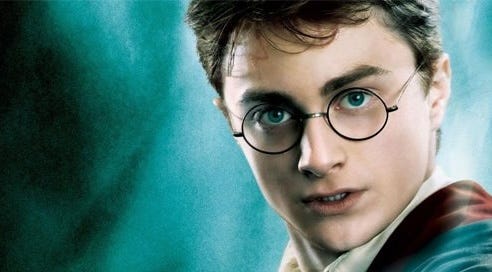

I asked whether the person had ever been tempted to read the Harry Potter books.

Oh no, not at all.

Anyway, it’s for the Harry Potter books that J.K. Rowling’s use of overripe speech tags has become a thing. Much online sniggering has been occasioned by —

“Snape!” ejaculated Slughorn, who looked the most shaken, pale and sweating.

One Reddit thread begins by quoting, with some contempt —

“Add the pummelroot when the pot starts gushing,” Snape said lustfully.

And an article on Mint titled ‘The adverbs that gave JK Rowling away’ quotes Ben Blatt’s statistical analyses in Nabokov’s Favourite Word is Mauve: The Literary Quirks And Oddities Of Our Most-Loved Authors —

Hemingway, the minimalist, used only 80 adverbs in every 10,000 words while Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling (of whom Stephen King once said, “Ms Rowling seems to have never met one [adverbs] she didn’t like”) used them at the rate of 140 per 10,000.

Not that she needs it, but I’d like to speak up in J.K. Rowling’s defence.

In a previous entry about speech tags, I said that J.K. Rowling’s name often comes up in workshops — along with Mills & Boon — when we are talking about bad dialogue.

J.K. Rowling, a lot of people seem to assume, is a byword for bad writing.

What’s often said about her speech tags is that they are painfully superfluous. For example, someone might say, Rowling puts in quizzically when someone has just asked a question.

An example of this, from The Deathly Hallows, might be —

“Good day to you, Harry Potter’s relatives!” said Dedalus happily, striding into the living room.

Unless he’s being ironic, if it’s a good day, and he’s benefiting from that, Dedalus is going to be happy.

Another example —

‘Can’t do it,’ said Hestia tersely.

To say, instead, that Hestia said those words expansively would be nonsensical. They are terse words. It’s a terse sentence, leaving out the first person.

And one last example —

‘I miss my wand,’ said Hermione miserably.

In all three cases, you could argue that the dialogue has already done by implication what the speech tag only annoyingly confirms.

And this is my main point of unpicking.

J.K. Rowling is writing for inexperienced readers. Not bad readers, not at all — far from it. I would give just about anything for the kind of passionate absorption she gets from her audience.

The Harry Potter books are wonderful for getting children to love books who previously hated them. And the kind of reassurance and confirmation J.K. Rowling’s adverbs give is part of this.

J.K. Rowling’s isn’t short story writing for the New Yorker — by which I mean, short story writing for people who have read a lot of short stories, and who already know how New Yorker stories work, and that there are such things as epiphanies, and most of what happens in an epiphany goes unsaid.

Instead, this is writing that constantly says to the reader, You figured this out, and, look, you were right — how clever you are.

It does this on the level of plot, where the reader knows the danger Harry Potter is heading towards better than he does, but also on sentence level, where there isn’t only statement but a gentle reinforcement of statement.

‘I miss my wand,’ said Hermione miserably.

This is not bad writing. It’s appropriate writing — exactly appropriate for the readers Harry Potter was intended for.

By the time they get to The Deathly Hallows, they are a lot more experienced than when they started The Philosopher’s Stone, but it’s quite possible they’ve only been reading for five or six months, and that all they’ve read so far are the previous books in the series.

Even so, by including this kind of reassurance within her sentence structures — by letting her readers adverbially know that they’re on the right track, or nudging them back if they’re not — J.K. Rowling is, in my opinion, doing anything but bad writing.

This is an excellent essay, he wrote appreciatively.

This is good, Toby. Like most old stagers I too wince at the sight of superfluous adverbs and advise - er, emphatically - against them. But your analysis is both sharp and just. I was already nearly forty when Harry Potter was flying out of my bookshop, so immune to the charms of Rowling’s prose. My children and grandchildren, however, had never read Hemingway…