Beneath what Keith Richards said yesterday, I believe, is this —

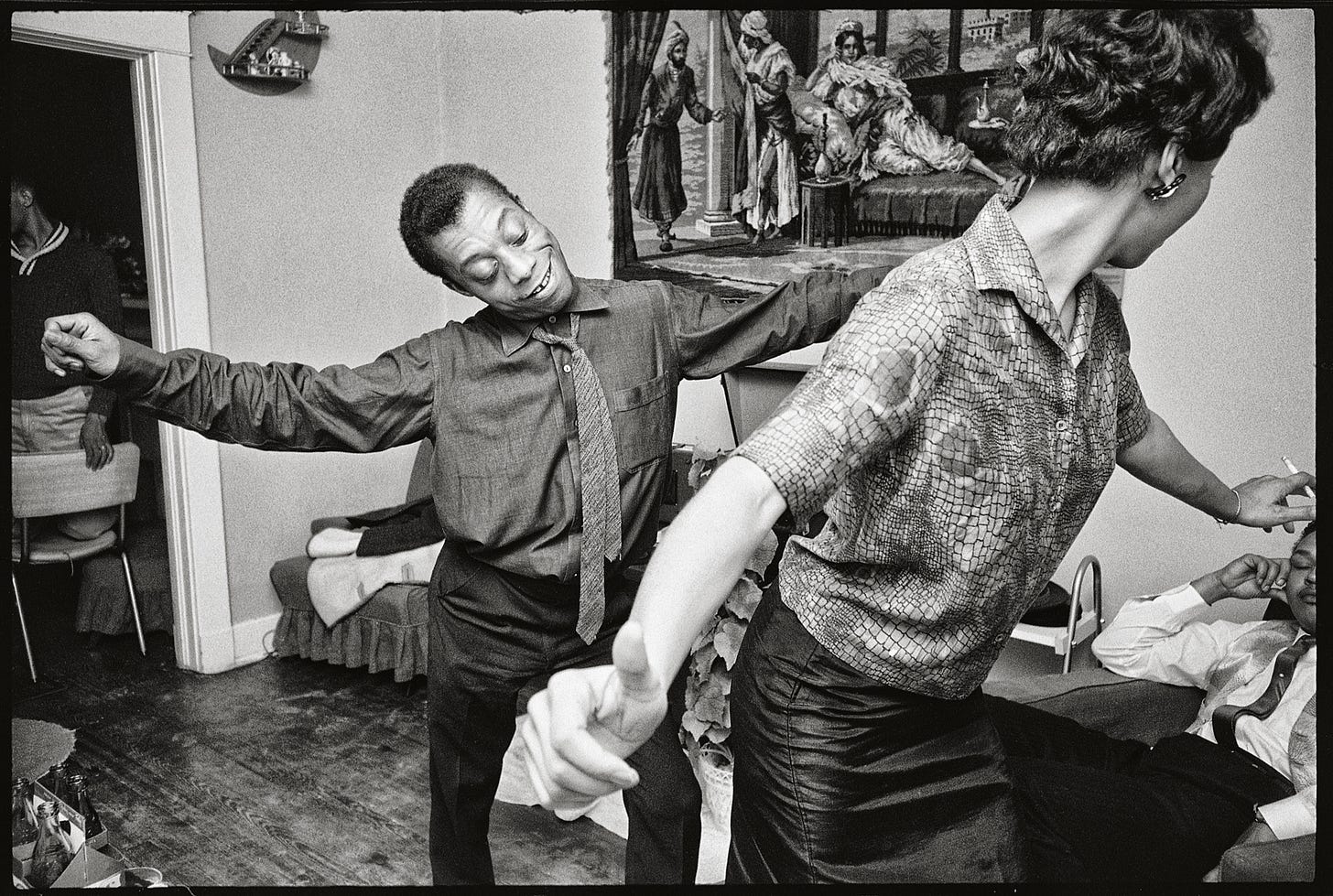

In all jazz, and especially the blues, there is something tart and ironic, authoritative and double-edged. White Americans seem to feel that happy songs are happy and sad songs are sad, and that, God help us, is exactly the way most white Americans sing them—sounding, in both cases, so helplessly, defencelessly fatuous that one dare not speculate on the temperature of the deep freeze from which issue their brave and sexless little voices. Only people who have been “down the line,” as the song puts it, know what this music is about….

James Baldwin wrote this in The Fire Next Time, in 1963, and when I first read it I couldn’t believe it was even sayable.

It’s probably the single most foundation-shaking critical statement — truth — I’ve ever read.

Of course.

What could be flatter, deader than happy songs that are happy?

The problem is, we now don’t listen to the music that Baldwin is talking about. For example, barbershop quartets — God help us. For example, almost all parlour music.

1963 was when, through The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, the ‘British invasion’ began — of white artists doing their best to sound tart and ironic, authoritative and double-edged.

According to Keith Richards, in the excellent TV documentary Little Richard: King and Queen of Rock’n’Roll —

The America before the British invasion was a totally different place. Everything that went before they sort of threw in the garbage can. It’s amazing how, because this is the stuff we’re playing back to them.

But the blues revival had been building up in Britain, and before that the trad jazz scene, for years.

As if trying in advance to address Baldwin’s humiliating criticism, those musicians set themselves to school to Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters… (how can I even begin?)

Self-consciously, studiously, and very often awkwardly and acquisitively, they began the work of making sure that never again would their happy songs be merely happy and sad songs merely sad.

Which is a lesson that always needs learning — in every phrase and paragraph.

In the same pages of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin continues —

I think it was Big Bill Broonzy who used to sing “I Feel So Good”, a really joyful song about a man who is on his way to the railroad station to meet his girl. She’s coming home. It is the singer’s incredibly moving exuberance that makes one realise how leaden the time must have been while she was gone.

If you want show, don’t tell, here it is.

There is no guarantee that she will stay this time, either, as the singer clearly knows, and, in fact, she has not yet actually arrived. Tonight, or tomorrow, or within the next five minutes, he may very well be singing “Lonesome in My Bedroom”, or insisting, “Ain’t we, ain’t we, going to make it all right? Well, if we don’t today, we will tomorrow night.”

I’m reminded of Jacques Brel’s ‘Matilde’ — in which the singer’s euphoria at his girl’s return becomes almost psychotic, and our belief in his future happiness is an anguished zero.

The chansonniers and folksingers of Europe (including Britain) knew all about what Baldwin was saying. The doubleness of life. Saudade and lilt. It was a specific American protestant puritan tradition that had deliberately obliterated that knowledge.

Baldwin widens his critique —

White Americans do not understand the depths out of which such an ironic tenacity comes, but they suspect that the force is sensual, and they are terrified of sensuality, and do not any longer understand it. The word “sensual” is not intended to bring to mind quivering dusky maidens or priapic black studs. I am referring to something much simpler and much less fanciful. To be sensual, I think, is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread. It will be a great day for America, incidentally, when we begin to eat bread again, instead of the blasphemous and tasteless foam rubber that we have substituted for it. And I am not being frivolous here, either.

Here, I think, he’s referring to W.C. Handy’s ‘Loveless Love’, as sung by Billie Holiday.

From milk-less milk and silk-less silk

We are growing used to soul-less souls

And this must be what Keith Richards means when he says —

Those [Little Richard] records had a big effect on me and my generation. They threw a whole different light on life, and its possibilities.

Last word goes to James Baldwin —

To be sensual, I think, is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.

Just as all literature may come from Gogol’s Overcoat (paraphrasing Lahiri’s Namesake ), all modern music comes from the jazz and blues you mention. Baldwin must be turning in his grave because it’s no longer just Whites. Modern Hip Hop, hello? Forget color and race, Ai music are you kidding?! I hear Oasis is back. Has culture been dead that long already? Are we going backwards to jump forward?