On How to Take Writing Advice

That's Not Bespoke

It’s not all about you.

For a time, this was my parents’ catchphrase. What they said to me most often.

And they weren’t wrong.

But many of us tend to believe — as a default — that it is all about us.

I used to have the illusion, which I know lots of people share, that the world was being built just around the corner from where I could see.

Until I arrived, and it came into sight, it was just scaffolding and panic.

On the way to school, walking up from Bedford Central Bus Station, I’d suddenly start to sprint — in hopes of catching the builders trying to finish off the top left hand corner of a tower block.

The builders were minions before the fact. They were scurrying constructors whose job was to maintain my illusion that the whole of the rest of the world — the Pyramids, North Yorkshire, the Harpur Shopping Centre — really existed.

Even though it didn’t — or only did potentially.

If I went there, to try to buy a notepad from WHSmiths, they’d have to make it, and WHSmiths, and the notepad.

This is a kind of opposite to If you build it, they will come — from Field of Dreams.

If you go, they will have to build it.

And there’s another opposite, which is the collapse of this it’s-all-about-me into ego-death and depression.

I’m the only thing in the world that isn’t real.

Everything else is solid, valid.

Not this ghost.

But that’s not what I’m thinking about today.

Avoid that.

Recently, I’ve put out some general advice — for example 9 Things Not to Do in Your First Novel’s First Draft — and I’m very aware how it’s likely to be received.

Individually.

Most writers, when they read a piece of advice, immediately check it against their current project — or check their current project against it.

But that’s exactly what I’m doing.

Are you saying I can’t do that?

Why are you attacking me?

I do this myself.

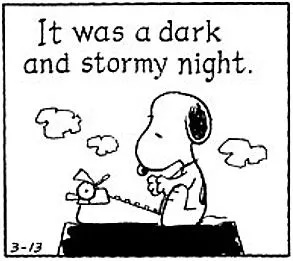

It’s hard to hear, Never open a novel with bad weather and not apply it to the mild drizzle at the beginning of your first chapter.

This is even more the case when some guy on the internet comes out with Don’t Write in the Present Tense or the Second Person.

In bold, even.

But all writing advice that isn’t spoken directly to you, that isn’t given in response to a close and committed reading of what you’ve written, isn’t about you.

It might seem that it is.

It’s not.

You can apply it, of course.

You can see it as a narrow alley or a broad street built just for you. With bespoke tower blocks.

And hopefully, it’s a useful way to go this afternoon or tomorrow morning.

But the real world solidly exists before you happen upon it.

Really useful things you hear are more likely to be useful in a year or five’s time.

And so my advice about advice is —

Yes, fine, react by panicking. React by applying it immediately to the thing you’re working on. React personally.

After that, though, try to take a view from further off.

Ask, Why would someone say that in general?

Ask, Why would they think it worth saying, of all the things they might say?

Ask, Why would they say that exactly as they have said it?

You will learn a lot more by taking this calmer look. Because you’ll be thinking about general principles rather than immediate practice.

With bad weather at the start of novels, it may be because the person giving the advice has read a number of not-very-good unpublished novels that begin with crass thunderstorms.

Or they’ve heard no dark and stormy nights given as advice a few times by other writers they respect, and are adding their voice to that particular chorus.

Or they tried it themselves, and realised it was rubbish in their version.

Or maybe, just perhaps, they are trying to guide you toward opening your novel in a more original and startling way.

With avoiding the Present Tense and Second Person — there’s too much to say. They’re anything but bad in themselves, but they are treacherous for first novelists.

What’s the single piece of advice that’s stayed with you the longest, and served you the best?

Cut 100 words from every page of your m/s. From one of my early mentors, Robert Edric.

Be bold, be dedicated, be authentic. But permit truancy, as brains keep writing after fingers stop typing.