‘It catches something, under there somewhere… it catches hidden things.’

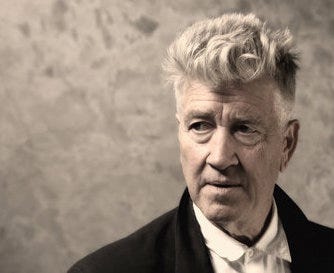

That’s what David Lynch is quoted as saying of Stanley Kubrik’s Lolita (1962) in David Bromwich’s review of Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams’ Kubrik: An Odyssey in the 26th September issue of the London Review of Books.

Lolita — a film I have only ever heard bad things about, and which I’ll now have to watch.

Here is the full quote —

Lolita was named by David Lynch as one of his favourite films, and when the director of Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive was asked why, he said: ‘It catches something, under there somewhere… it catches hidden things.’

Raymond Carver had a three-by-five card taped to the wall beside his writing desk with these words on it —

‘…and suddenly everything became clear to him.’

They were, Carver said, a fragment of a Chekhov story.

I am thinking of pinning up a three-by-five card that reads —

‘…it catches hidden things.’

Haphazardly, I’ve been heading toward a theme — yesterday, and a few times before, and that’s the mystery.

I could say something more accurately ironic, such as the relationship between completed writing and inarticulacy.

But I’ll let it go as something bigger, vaguer and more embarrassing than Donald Barthelme’s the Not-Knowing.

So far, as advice, it — what I’ve been trying to get at — has been about allowing yourself not to write in an informed, sensible way.

I encourage splurge.

Yesterday, I was suggesting babble as a stage before laying sense out in the light.

This Lynch quote is about something weirder than that. And I find it convincing; reminding me of the strongest things I’ve read.

It’s the idea that, even when you’ve done all you can, finished that final draft, the most and best of your prose can remain unknown to you — and that being a good thing.

This is, I’d say, more than subtext.

Subtext is something a writer can consciously, even cynically, lace in to a story.

Closer to what I’m suggesting is the painter Francis Bacon’s statement —

Painting is the pattern of one’s own nervous system being projected on canvas.

And Bacon’s desire that the viewer’s nervous system be, for a moment, similarly patterned.

What this must mean is that the story never unveils those hidden things, because it can’t.

Everything doesn’t suddenly become clear to either the writer or the reader.

Perhaps this is the opposite of epiphany — that a story ends with a greater sense of what’s unsayable.

Unsayable, but not incommunicable, because Lynch twice insists on catches.

It can be trapped in there, whatever it is, it can be confined by words or images or hardened clay or music.

Not all, perhaps not many, writers are going to want to permit themselves to do something so unnerving.

‘…it catches hidden things.’

It could last a writer years, that hint.

It would be really interesting/enlightening/instructive, I think, to take every post you write (and indeed every ‘Office Hours’ post George Saunders writes) and apply them not to fiction but to memoir. About fifty percent of the content would, sure, translate directly. But adapting/riffing off the fifty percent that doesn’t translate might produce a theorising about memoir more nuanced than anything currently out there (or anything I’ve found, anyway - but maybe there’s some Memoir Theory Genius I just haven’t come across…).

Always trying to grasp it but it's a slippery thing.