As writers, we try very hard to describe things clearly, so readers can picture them.

We may hesitate for a long time over whether a morning wall should be pale or pale grey or greyish white or light grey.

But what do — or rather, what can — a reader end up seeing?

Are there limits to the amount of detail they can extrapolate from a very small number of visual cues?

I realise that this is something about which it is dangerous to generalise.

All brains are different. All readers are unique. Some are likely not to see images at all but just to receive practical information to be appropriately filed.

She wore a 1940s-style grey skirt suit with a black beret.

Equates to —

She is well dressed and stylish in an old-fashioned way.

Some readers, however, might — I’m guessing — see for a moment a good approximation of a 1940s-style grey skirt suit and, first imagining the character’s face, will place a black beret on their head.

This is dependent on the reader’s pre-existing knowledge 1940s fashions, and perhaps — for some — of what exactly a beret is.

A costume designer or a milliner who has recreated or sewn a costume for a historical drama will almost certainly be seeing far more detail (stitching, lining) than someone who has gone through life paying very little attention to women’s clothes.

From what I’ve read of neuro stuff — i.e., The Ego Tunnel by Thomas Metzinger (2009) — most of us humans manage to trick ourselves into believing we live in a far richer sensory imaginarium than is really available to us.

I am fascinated by patterns, and how flukily we perceive them. For example, if we look at wallpaper covered in regularly spaced fleur-de-lys, do we see much of it at all? Or do we register a shape, the intervals between it when it recurs, and then perform the mental equivalent of saying etcetera etcetera, blurring off some splodges to the edge of our visual field?

Stand gazing in front of a black and white Bridget Riley. It can become unbelievably trippily psychedelic. Pink and yellow zigzags and reaching out tentacles.

There isn’t time to go into this. But if I write —

The wallpaper in front of you consists of crisply printed one inch wide white and black stripes .

— what do you see?

Here’s some space to see it in. Scroll down afterwards.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

What did you see, and how clearly, given that I haven’t told you whether the stripes are horizontal or vertical or diagonal?

What happened at the edges?

I think it’s interesting that although most writers have a sense of what vivid description is, and how much vivid they themselves are comfortable with putting on the page, I don’t think that they give much thought to mental imagery itself — that is, to the possibility of precisely controlling someone else’s mental imagery through language.

Probably because they stop at All readers are unique and guess any further speculation won’t get them very far, or repay their time.

How many adjectives to include is a verbal and stylistic decision, rather than one of adding more pixels to the reader’s mental HDTV.

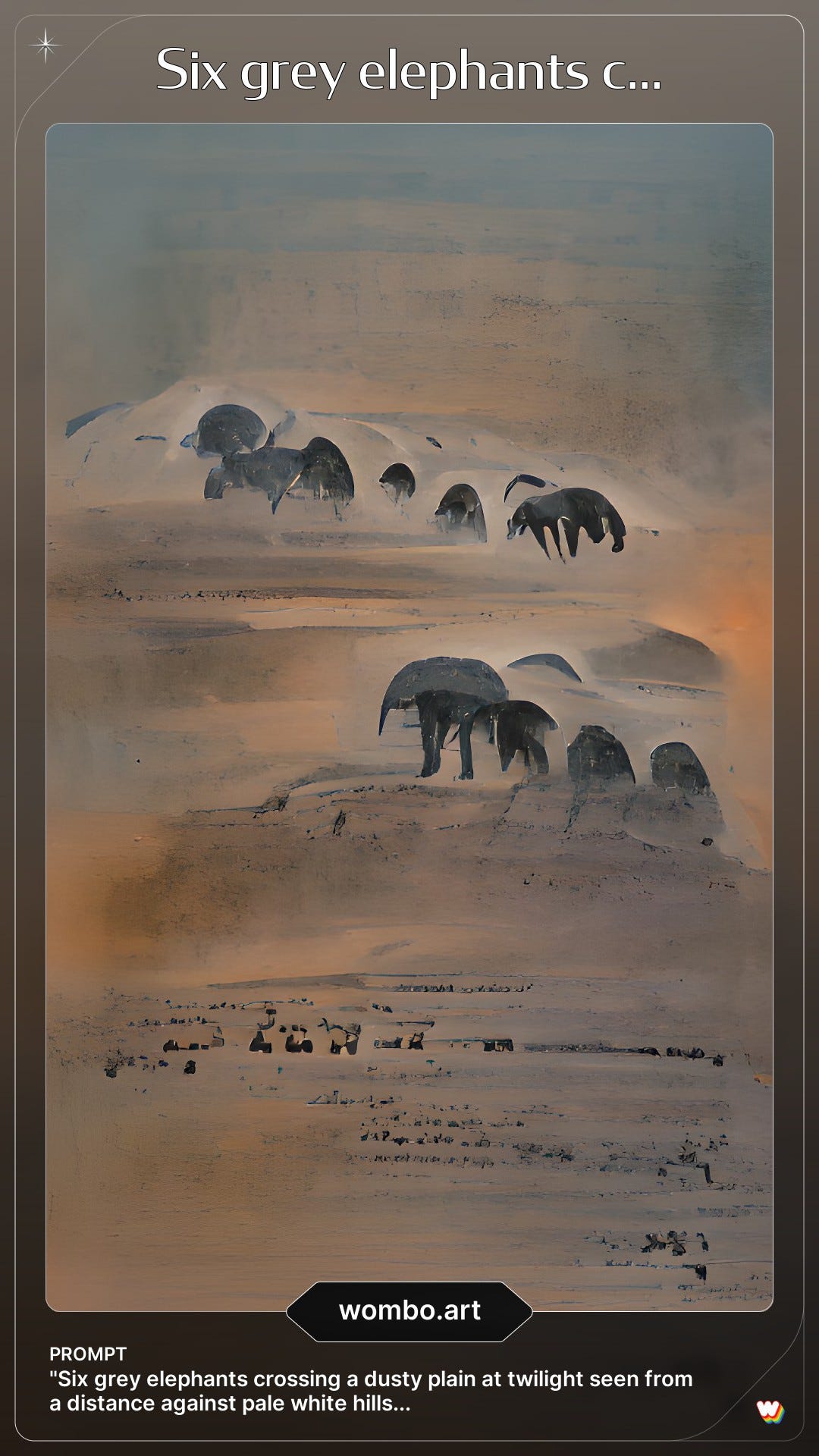

Unscientifically, I have been playing around with AI for a couple of years. Because it seems to me that there is something to be learned from the amount of visual information that a non-human entity, even one trained on previous human-created photographs and images, can extract from a single line of description.

My test sentence, my offered prompt, has been —

“Six grey elephants crossing a dusty plain at twilight seen from a distance against pale white hills...”

On 12 January 2022, this is what wombo.art came up with —

Laugh if you will, but I’m going to return to this.

Around nine months later, on 19 October 2022, Dall-E shot back the more photorealistic —

Again, we can laugh now at those five and six leg shaped things with increasingly less accurate elephant heads, left to right..

Just now, ChatGPT returned (from that exact same prompt, no words changed) —

Which is bizarre, given that ten is not six. And that the hills in the background are anything but pale and white. And that ChatGPT is mean to crap on previous AI.

To refine this image, by giving further prompts, would be to undermine the experiment.

I want to know what’s in those few descriptive words — inspired by the title of Hemingway’s short story ‘Hills Like White Elephants’.

And what do I think I’ve learned from this?

“Six grey elephants crossing a dusty plain at twilight seen from a distance against pale white hills...”

Apart from the fact that ChatGPT is stylistically tending toward poster art, whilst Dall-E was more travel photography, and wombo.art was Oil Landscape Painting with a Palette Knife 101, I would say that my own mental images are closer to the earlier and more primitive iterations of AI.

What goes on in my head, as far as I can describe it, is more woozy and smeary and flickering and morphing than self-consistent and boxed.

If I am given a sentence to read such as —

He walked along, his cocker spaniel close behind him.

— then I know I don’t consistently maintain a four-legged creature in my head thereafter.

They continued down the narrow path through the cornfield.

I have a sense of a taller male figure, as described in previous sentences, and then of a lower down hairy doggish shape that moves on leg-things which, if they’re described, I’ll bring into focus.

The fictional dog has an area for legs and an area for a tail, but I am awaiting further information before I commit to —

The dog’s feathery tail flapped delightedly behind it.

Have you read Peter Mendlesund's "What We See When We Read"? That really fascinated me.

In my head, your prompt was giving me an image in my head that was a cross between Wombo and the Wall-E image.

This diary entry has triggered memories of these works, which might provide useful further reading:

- 'How Words Do Things With Us' - Ch. 8 of Daniel Dennett's seminal tome 'Consciousness Explained'.

- 'The Science of Storytelling' by Will Storr.

- New Scientist Essential Guide #12 - 'Consciousness - Understanding the Ghost in the Machine'

- 'Reality - A Very Short Introduction' by Jan Westerhoff. (One topic in the OUP's excellent VSI series, with 'Perception' and 'Cognitive Neuroscience' being two related others.)

Finally – just for fun – test how accurate the hallucination machine inside your own skull is: https://youtu.be/vJG698U2Mvo?si=GFxRV4m1cJKSN5NA