This is an introduction that did make it into print. Also (like the Houellebecq) of a French novel — one of the best.

I also included it in my non-fiction collection, Mutants, which was published by Seagull Press.

Unlike a lot of what I write, I still agree with this. Which is why I’m sharing it now.

We use books to define and redefine ourselves.

How do you think about your life? It’s not a simple question. How do you introduce enough distance between yourself, this person who has lived your life, and yourself, this person you are, so as to be able to think of them? Not think objectively, that is definitely impossible, but with some perspective and therefore, you might hope, some small chance of getting the general outlines at least right. Joris-Karl Huysmans’ Against Nature gives instances, or rather is an instance, I would say, of two of the most commonly used methods of self-thinking.

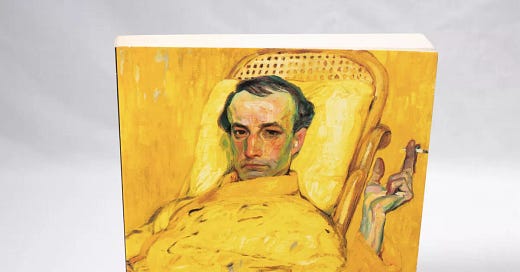

Before I get to them, however, I would like briefly to characterize Huysmans’ book. Against Nature is inseparable from its listless protagonist, the Duc Jean des Esseintes. Like him, Against Nature is frail, anaemic, ennervated, perverse. Formally, Huysmans does everything he can possibly do to undermine any expectation that this novel might contain a story. He begins with a Prologue that tells us, essentially, all the most interesting things that have happened to des Esseintes – and it also tells us that these things have happened already, that we won’t be hearing about them in this book except in retrospect. There is enough implied incident in these pages to fill an entire novel, and Huysmans throws it away. By the time the Prologue finishes, des Esseintes has exhausted all his desires – and is therefore the perfect subject for a novel with no narrative tension, no quest, with nothing but a voice, an attitude and a desire disconcert.

Throughout Against Nature two tendencies are in opposition, categorization and flow; sometimes flow will come to dominate, sometimes categorization, but never for long – rarely for more than a paragraph. Good examples of both tendencies can be found in almost every chapter, but one of the best is the ‘collection of liqueur casks’ that des Esseintes calls his ‘mouth organ’. This seems quite self-consciously to be an attempt to reconcile the two tendencies in one object. The mouth organ, like much in the novel, is based upon the principle of analogy. ‘Indeed, each and every liqueur, in his opinion, corresponded with the sound of a particular instrument. Dry curacao, for instance, was like the clarinet with its piercing, velvety note…’ Yet even in this first example, there is a slip towards flow – the taste of curacao is categorized as ‘like the clarinet’ but to illustrate this the word ‘velvety’ is used. In other words taste is like sound is like touch. This confusion of the senses, this fluid crossing of the boundaries separating them, is characteristic of that very poetic condition, synaesthesia. Baudelaire’s sonnet ‘Correspondances’ is the source: ‘Les parfums, les colours et les sons se repondent.’ [‘Scents, colours and sounds all correspond.’]

Early on in Against Nature, des Esseintes makes close correspondences between books and colours. ‘The drawing room, for example, had been partitioned off into a series of niches, which were styled to harmonize vaguely, by means of subtly analogous colours that were gay or sombre, delicate or barbarous, with the character of his favourite works in Latin and French.’ Later, books are likened to food, to drawing, to painting, to the sick and dead body – and the flow of analogy doesn’t stop here, jewels are experienced as food, food as the sick body, etc. In order to try and categorize this flow, des Esseintes and Huysmans come up with similar strategies: des Esseintes divides his life self-consciously into periods; Huysmans divides des Esseintes’ life into chapters. And these are examples of the first method most people use to understand their lives.

It is impossible to think about your life as an unbroken flow, from birth, or from when your memories begin, up until the point you have now reached. In order to understand it in any way at all, you have to categorize it, either by dividing it up into periods (infancy, childhood, school, twenties, etc.) or by gathering parts of different periods together under implicit chapter-headings (education, travel, sex, love). Both of these, of course, involve the distillation of experiences, just as the liqueurs in the mouth organ have been distilled.

What is fascinating about des Esseintes is how self-consciously he attempts to categorise the flow of his own existence – the dandy, by definition, is someone attempting to turn their life into a work of art. There is a clear collaboration between des Esseintes and his biographer, Huysmans, but one of the perverse ways in which the book they share seems to work is that the life has been lived in order to facilitate the form of its telling. We know this is not the case, and the illusion should backfire: the writer, really, surely, is making the subject convenient for himself. Yet it is clear that des Esseintes just as much as Huysmans shapes the book by living his life so clearly in periods, which, eventually, will be incorporated into chapters. The interplay between des Esseintes’ periods and Huysmans’ chapters is what gives the book its distinctive form – it is a syncopation, the one not always lining up with the other: some chapters contain several periods, some only one. This is in many ways the book’s only formal tension – otherwise, the novel would resemble a gigantic escalating list. (If one were being really cheeky, one could describe des Esseintes as a prototype Nick Hornby list-boy.) There is almost no plotting as such: the death of the tortoise, which is forgotten then discovered, dead, is one of the few incidents worth mentioning.

It’s worth saying that there is nothing at all Natural about viewing a life as divided up into periods. But this tendency has been on the increase throughout human history. The more people there are with some control over their lives, the more self-consciously they will exercise that control. Many people in the past have lacked the chapter-making capacity (or privilege) altogether, and many still do: their life is their life, as it is now so it will continue to be. Popular psychology has popularized the idea of the quantum existence, the life lived in discrete packets of energy – chapters. The message of Oprah is the same message as Rilke’s ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’: ‘You must change your life.’ For unless you see your life as having chapters, you will have no way of changing it, because you will be unable to believe it can be changed, because – in turn – you won’t be able to perceive the points in the past where it has changed.

The other method of self-thinking comes through comparison of the self with what is known of the selves of others. Against Nature is a book in which and through which and also against which many people have defined themselves. It is, in many ways, a deliberate primer for the personality. Des Esseintes is at once one of the most attractive and repulsive characters in literature. Or perhaps not at once but at different periods, and not periods in his life but in our own. The world-view of des Esseintes is adolescent: contemptuous of the everyday, easily bored, hypersensitive, sulky. As he cries out at one point, like a teenager refusing to go out with their parents: ‘But I just don't enjoy the pleasures other people enjoy!’ And the character of des Esseintes, therefore, is far more likely to attract one when one is adolescent, and to repel one more and more the further one gets away from that frustrating and clumsy chapter. What Against Nature does is give a very precise series of comparisions-to-be-made. For example, des Esseintes’ love of the prints of Jan Luyken:

‘He possessed a whole series of studies by this artist in lugubrious fantasy and ferocious cruelty: his Religious Persecutions, a collection of appalling plates displaying all the tortures which religious fanaticism has invented, revealing all the agonizing varieties of human suffering – bodies roasted over braziers, heads scalped with swords, trepanned with nails, lacerated with saws, bowels taken out of the belly and wound on to bobbins, finger-nails slowly removed with pincers, eyes put out, eyelids pinned back, limbs dislocated and carefully broken, bones laid bare and scraped for hours with knives.’

This, I would guess, apart from the deep-in-adolescence, is a moment of separation between the reading self and that being described. ‘No,’ the reader is likely to think, ‘here we part company – there is no way I could live with such images.’ Of course, the black-bedroom inhabiting, Marilyn Manson listening, gore-fascinated adolescent is likely to say, ‘Cool,’ and type JAN LUYKEN into their favourite search engine.

One of the tensions that replace narrative drama in Against Nature is that between novelist and character. It’s pretty clear that there is a separation between des Esseintes and Huysmans, and this is clearest in their sense of humour: des Esseintes’ is amused by cruelty and little else; Huysmans is sly and brilliant humorist. He follows the Luyken description with this little deadpan gem: ‘These prints were mines of interesting information and could be studied for hours on end without a moment’s boredom…’

Against Nature is a tempting book, one that, in many sections, attempts to draw the reader into closer proximity with evil. Yet by doing this, and also by granting that authors, books and readers may not all be on the side of the angels, Huysmans reveals himself to be an extremely moral writer. As he notes —

‘The truth of the matter is that if it did not involve sacrilege, sadism would have no raison d’etre; on the other hand, since sacrilege depends on the existence of religion, it cannot be deliberately and effectively committed except by a believer, for a man would derive no satisfaction whatever from profaning a faith that was unimportant or unknown to him.’

Which may explain why Against Nature is one of the least perverse and most autobiographically useful novels ever written.