Yesterday I didn’t reach published published.

I didn’t get to the first book with just my name on it.

Which was Adventures in Capitalism in 1996, over a decade after I’d started to think writing was my thing.

In my application for the UEA Creative Writing MA in 1994, I said I wanted to write another novel — which would have made five and a half.

At the interview, with Rose Tremain, I said I had changed my mind and was intending — if they gave me a place — to write short stories.

I’d decided to put a pause on trying to get published. It was messing me up with the wrong kind of anxiety. Instead, I would concentrate on trying to get better at writing — whatever that meant, whatever that took. Afterwards, I’d go back to novel and novel and novel, with fingers crossed.

This was the right decision.

It was partly because I was writing short short stories — four pages long — that I ended up being included in Malcolm Bradbury’s anthology.

I didn’t really think they counted as stories at all. They were deliberately ridiculous. That’s why I bundled them into a mini-collection.

I hadn’t read Lydia Davis or Diane Williams, or heard of flash fiction.

What I had heard was that Ian McEwan, when he was on the MA, tried to write one story a week.

So I tried to write one story a week — sometimes on the train up from Liverpool Street.

I listened on my Walkman to Suede’s Dog Man Star and all of Steely Dan.

I wrote in biro, in a spiralbound reporter notepad.

My main aim was to start writing longer stories but in order to keep on schedule, some of them still ended up too short.

Still, they were starting to add up to something.

After Malcolm Bradbury said he would put four of the four-pagers in his anthology Class Work, I knew there was a possibility publishers would be interested in me.

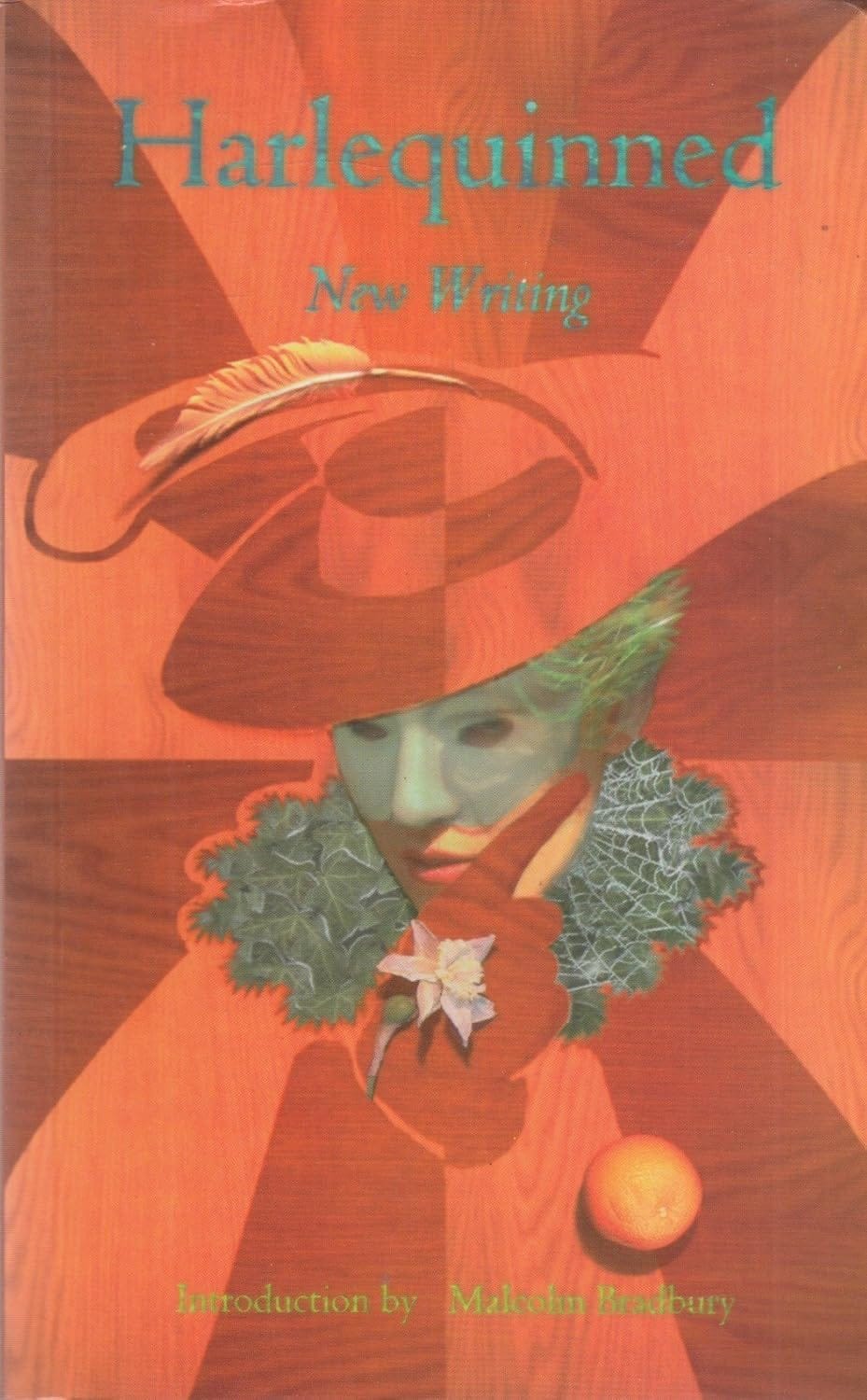

I was also appearing in the annual UEA Creative Writing anthology, and there would be readings and publicity for that.

But I didn’t switch to a novel. Until the end of the academic year, I was determined to write one story a week.

And they began to grow in length.

The breakthrough, as far as my agent was concerned, came when I wrote and sent her a ghost story called ‘Launderama’. Mic loved that one, and another called ‘Moriarty’.

Both were long enough for me to think of as a proper stories.

I hadn’t got a publisher by this point. I was working near Hanger Lane doing subtitles for ITV and Channel 5 programmes. I often did episodes of Cilla Black’s Blind Date and Bruce Forsyth’s The Price Is Right.

How finally getting published happened was —

In the autumn of 1996, Mic, my agent, heard from Neil Taylor, an editor at Secker & Warburg. He said he’d read my stories in a proof copy of Class Work, and wanted to see more, and was interested in making a pre-emptive offer.

Mic wasn’t keen on pre-empts but was prepared to consider it.

A month earlier, no-one had been interested in me. Now I had publishers getting in touch. Malcolm Bradbury and Jon Cook had been talking me up. Something was building. But I didn’t trust it — I’d been disappointed many times by nearly and almost.

On 20th September 1995, my diary entry begins —

Mic phoned around 11am. Secker have offered me a two book deal at £15,000. She turned it down.

The following evening, I was doing a reading with other writers from the UEA course, to promote our year’s annual anthology, Harlequinned — a rarity, if you find one.

John Boyne (who later wrote The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas) was one of the readers, and Bo Fowler (Skepticism Inc), Jeanette Jenkins (Firefly), and Richard Beard (The Day that Went Missing). We were at Waterstones in Earls Court, being introduced by Andrew Motion.

Neil Taylor was there, and afterwards he and I went to a pub opposite the station.

This was when I knew I was going to get published, because I could tell Neil was scared someone else would get to me.

I made the mistake of mentioning I’d sent a typescript to an editor called Maggie McKernan who worked at Orion Books. She had been very encouraging — meeting me every time she read a new novel by me, but never liking them quite enough to publish.

Neil looked anxious when he heard me say I knew Maggie. On the pavement outside, he wanted reassuring that I wasn’t pissing him around. I told him I wasn’t.

Maggie said she liked the stories but they weren’t lyrical enough for her.

Secker raised their offer.

Neil ended up being my first editor, and publishing my first book.

Later, it turned out that Neil hadn’t been entirely alone in talent spotting me. His girlfriend, Alison Craddock, the publicist at Hodder & Stoughton, had given him a proof copy of Class Work — and had told him he should read my stories. I was good, she thought.

I like to imagine my big break came through pillow talk.

Interesting makes me want to read what you wrote. I’m having trouble coming up with so many ideas.

I love seeing you in my inbox every morning. There's something comforting in the way you write. Thank you.